(Guest Post by Jason Bedrick)

Last week, the Cato Institute held a policy forum on school choice regulations (video here). Two of our panelists, Dr. Patrick Wolf and Dr. Douglas Harris, were part of a team that authored one of the recent studies finding that Louisiana’s voucher program had a negative impact on participating students’ test scores. Why that was the case – especially given the nearly unanimously positive previous findings – was the main topic of our discussion. Wolf and I argued that there is reason to believe that the voucher program’s regulations might have played a role in causing the negative results, while Harris and Michael Petrilli of the Fordham Institute pointed to other factors.

The debate continued after the forum, including a blog post in which Harris raises four “problems” with my arguments. I respond to his criticisms below.

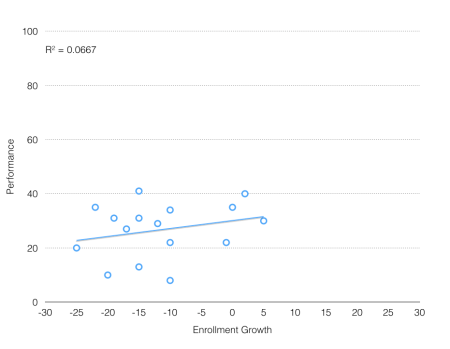

The Infamous Education Productivity Chart

Problem #1: Trying to discredit traditional public schools by placing test score trends and expenditure changes on one graph. These graphs have been floating around for years. They purport to show that spending has increased much faster than expenditures [sic], but it’s obvious that these comparisons make no sense. The two things are on different scales. Bedrick tried to solve this problem by putting everything in percentage terms, but this only gives the appearance of a common scale, not the reality. You simply can’t talk about test scores in terms of percentage changes.

The more reasonable question is this: Have we gotten as much from this spending as we could have? This one we can actually answer and I think libertarians and I would probably agree: No, we could be doing much better than we are with current spending. But let’s be clear about what we can and cannot say with these data.

Harris offers a reasonable objection to the late, great Andrew Coulson’s infamous chart (shown below). Coulson already addressed critics of his chart at length, but Harris is correct that the test scores and expenditures do not really have a common scale. That said, the most important test of a visual representation of data is whether the story it tells is accurate. In this case, it is, as even Harris seems to agree. Adjusted for inflation, spending per pupil in public schools has nearly tripled in the last four decades while the performance of 17-year-olds on the NAEP has been flat.

Producing a similar chart with data from the scores of younger students on the NAEP would be misleading because the scale would mask their improvement. But for 17-year-olds, whose performance has been flat on the NAEP and the SAT, the story the chart tells is accurate.

Voucher Regulations Are Keeping Private Schools Away

Problem #2: Repeating arguments that have already been refuted. Bedrick’s presentation repeated arguments about the Louisiana voucher case that I already refuted in a prior post. Neither the NBER study nor the survey by Pat Wolf and his colleagues provide compelling evidence that existing regulations are driving out potentially more effective private schools in the Louisiana voucher program, which was a big focus of the panel.

Here Harris attacks a claim I did not make. He is correct that there is no compelling evidence that regulations are driving out higher-quality private schools, but no one claimed that there was. Rather, I have repeatedly argued that the evidence was “suggestive but not conclusive” and speculated in my presentation that “if the enrollment trends are a rough proxy [for quality], though we can’t prove this, then it would suggest that the higher-quality schools chose not to participate” while lower-quality schools did.

Moreover, what Harris claims he refuted he actually merely disputed – and not very persuasively. In the previous post he mentions, he minimized the role that regulation played in driving away private schools:

As I wrote previously, the study he cites, by Patrick Wolf and colleagues, actually says that what private schools nationally most want changed is the voucher’s dollar value. In Louisiana, the authors reported that “the top concern was possible future regulations, followed by concerns about the amount of paperwork and reports. When asked about their concerns relating to student testing requirements, a number of school leaders expressed a strong preference for nationally normed tests” (italics added). These quotes give a very different impression that [sic] Bedrick states. The supposedly burdensome current regulations seem like less of a concern than funding levels and future additional regulations–and no voucher policy can ever insure against future changes in policy.

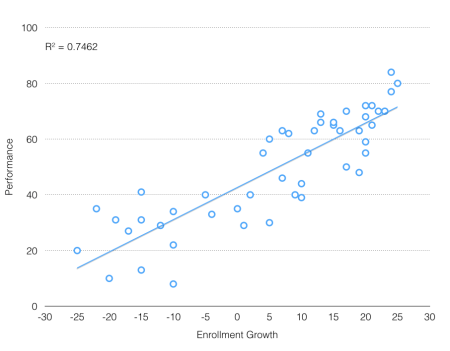

Actually, the results give a very different impression than Harris states. The quote Harris cites from the report is regarding the concerns of participating schools, but the question at hand is why the nonparticipating schools opted out of the voucher program. Future regulations was still the top concern for nonparticipating schools, but current regulations were also major concerns. Indeed, the study found that 9 of the 11 concerns that a majority of nonparticipating private schools said played a role their decision not to participate in the voucher program related to current regulations, particularly around admissions and the state test.

Source: ”Views from Private Schools,” by Brian Kisida, Patrick J. Wolf, and Evan Rhinesmith, American Enterprise Institute (page 19)

Nearly all of the nonparticipating schools’ top concerns related to the voucher program’s ban on private schools using their own admissions criteria (concerns 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 11) or requiring schools to administer the state test (concerns 6, 9, 10, and possibly 7 again). It is clear that these regulations played a significant role in keeping private schools away from the voucher program. The open question is whether the regulations were more likely to drive away higher-quality private schools. I explained why that might be the case, but I have never once claimed that we know it is the case.

Market vs. Government Regulations in Education

Problem #3: Saying that unregulated free markets are good in education because they have been shown to work in other non-education markets. […] For example, the education market suffers from perhaps the worst information problem of any market–many complex hard-to-measure outcomes most of which consumers (parents) cannot directly observe even after they’ve chosen a school for their child. Also, since students can realistically only attend schools near their homes, and there are economies of scale in running schools, that means there will generally be few practical options (unless you happen to live in a large city with great public transportation–very rare in the U.S.). And the transaction costs are very high to switch schools. And there are equity considerations. And … I could go on.

Harris claims that a free market in education wouldn’t work because education is uniquely different from other markets. However, the challenges he lists – information asymmetry, difficulty measuring intangible outcomes, difficulties providing options in rural areas, transaction costs for switching schools – aren’t unique to K-12 education at all. Moreover, there is no such thing as an “unregulated” free market because market forces regulate. As I describe below, while not perfect, these market forces are better suited than the government to address the challenges Harris raises.

Information asymmetry and hard-to-measure/intangible outcomes:

Parents need information in order to select quality education providers for their children. But are government regulations necessary to provide that information? Harris has provided zero evidence that it is, but there is much evidence to the contrary. Here the disparity between K-12 and higher education is instructive. Compared to K-12, colleges and universities operate in a relatively free market. Certainly, there are massive public subsidies, but they are mostly attached to students, and colleges have maintained meaningful independence. Even Pell vouchers do not require colleges to administer particular tests or set a single standard that all colleges must follow.

So how do families determine if a college is a good fit or not? There are three primary mechanisms they use: expert reviews, user reviews, and private certification.

The first category includes the numerous organizations that rate colleges, including U.S. News & World Report, the Princeton Review, Forbes, the Economist, and numerous others like them. These are similar to sorts of expert reviews, like Consumer Reports, that consumers regularly consult when buying cars, computers, electronics, or even hiring lawyers – all industries where the non-expert consumer faces a significant information asymmetry problem.

The second category includes the dozens of websites that allow current students and alumni to rate and review their schools. These are similar to Yelp, Amazon.com, Urban Spoon and numerous other platforms for end-users to describe their personal experience with a given product or service.

Finally, there are numerous national and regional accreditation agencies that certify that colleges meet a certain standard, similar to Underwriters Laboratories for consumer goods. This last category used to be private and voluntary, although now it is de factomandatory because accreditation is needed to get access to federal funds.

None of these are perfect, but then again, neither are government regulations. Moreover, the market-based regulators have at least four major advantages over the government. First, they provide more comprehensive information about all those hard-to-measure and intangible outcomes that Harris was concerned about. State regulators tend to measure only narrow and more objective outcomes, like standardized test scores in math and English or graduation rates. By contrast, the expert and user reviews consider return-on-investment, campus life, how much time students spend studying, teaching quality, professor accessibility, career services assistance, financial aid, science lab facilities, study abroad options, and much more.

Second, the diversity of options means parents and students can better identify the best fit for them. As Malcolm Gladwell observed, different people give different weights to different criteria. A family’s preferences might align better with the Forbes rankings than the U.S. News rankings, for example. Alternatively, perhaps no single expert reviewer captures a particular family’s preferences, in which case they’re still better off consulting several different reviews and then coming to their own conclusion. A single government-imposed standard would only make sense if there was a single best way to provide (or at least measure) education, we knew what it was, and there was a high degree of certainty that the government would actually implement it well. However, that is not the case.

Third, a plethora of private certifiers and expert and user reviews are less likely to create systemic perverse incentives than a single, government standard. As it is, the hegemony of U.S. News & World Report’s rankings created perverse incentives for colleges to focus on inputs rather than outputs, monkey around with class sizes, send applications to students who didn’t qualify to increase their “selectivity” rating, etc. If the government imposed a single standard and then rewarded or punished schools based on their performance according to that standard, the perverse incentives would be exponentially worse. The solution here is more competing standards, not a single standard.

Fourth, as Dr. Howard Baetjer Jr. describes in a recent edition of Cato Journal, whereas “government regulations have to be designed based on the limited, centralized knowledge of legislators and bureaucrats, the standards imposed by market forces are free to evolve through a constant process of evaluation and adjustment based on the dispersed knowledge, values, and judgment of everyone operating in the marketplace.” As Baetjer describes, the incentives to provide superior standards are better aligned in the market than for the government:

Incentives and accountability also play a central role in the superiority of regulation by market forces. First, government regulatory agencies face no competition from alternative suppliers of quality and safety assurance, because the regulated have no right of exit from government regulation: they cannot choose a better supplier of regulation, even if they want to. Second, government regulators are paid out of tax revenue, so their budget, job security, and status have little to do with the quality of the “service” they provide. Third, the public can only hold regulators to account indirectly, via the votes they cast in legislative elections, and such accountability is so distant as to be almost entirely ineffectual. These factors add up to a very weak set of incentives for government regulators to do a good job. Where market forces regulate, by contrast, both goods and service providers and quality-assurance enterprises must continuously prove their value to consumers if they are to be successful. In this way, regulation by market forces is itself regulated by market forces; it is spontaneously self-improving, without the need for a central, organizing authority.

In K-12, there are many fewer private certifiers, expert reviewers, or websites for user reviews, despite a significantly larger number of students and schools. Why? Well, first of all, the vast majority of students attend their assigned district school. To the extent that those schools’ outcomes are measured, it’s by the state. In other words, the government is crowding out private regulators. Even still, there is a small but growing number of organizations like GreatSchools, Private School Review, School Digger, andNiche that are providing parents with the information they desire.

Options in rural areas:

First, it should be noted that, as James Tooley has amply documented, private schools regularly operate – and outperform their government-run counterparts – even in the most remote and impoverished areas in the world, including those areas that lack basic sanitation or electricity, let alone public transportation. (For that matter, even the numerous urban slums where Tooley found a plethora of private schools for the poor lack the “great public transportation” that Harris claims is necessary for a vibrant education market.) Moreover, to the extent rural areas do, indeed, present challenges to providing education, such challenges are far from unique. Providers of other goods and services also must contend with reduced economies of scale, transportation issues, etc.

That said, innovations in communication and transportation mean these obstacles are less difficult to overcome than ever before. Blended learning and course access are already expanding educational opportunities for students in rural areas, and the rise of “tiny schools” and emerging ride-sharing operations like Shuddle (“Uber for kids”) may soon expand those opportunities even further. These innovations are more likely to be adopted in a free-market system than a highly government-regulated one.

Test Scores Matter But Parents Should Decide

Problem #4: Using all this evidence in support of the free market argument, but then concluding that the evidence is irrelevant. For libertarians, free market economics is mainly a matter of philosophy. They believe individuals should be free to make choices almost regardless of the consequences. In that case, it’s true, as Bedrick acknowledged, that the evidence is irrelevant. But in that case, you can’t then proceed to argue that we should avoid regulation because it hasn’t worked in other sectors, especially when those sectors have greater prospects for free market benefits (see problem #3 above). And it’s not clear why we should spend a whole panel talking about evidence if, in the end, you are going to conclude that the evidence doesn’t matter.

Once again, Harris misconstrues what I actually said. In response to a question from Petrilli regarding whether I would support “kicking schools out of the [voucher] program” if they performed badly on the state test, I answered:

No, because I don’t think it’s a wise move to eliminate a school that parents chose, which may be their least bad option. We don’t know why a parent chose that school. Maybe their kid was being bullied at their local public school. Maybe their local public school that they were assigned to was not as good. Maybe there was a crime problem or a drug problem.

We’re never going to have a perfect system. Libertarians are not under the illusion that all private schools are good and all public schools are bad… Given the fact that we’ll never have a perfect system, what sort of mechanism is more likely to produce a wide diversity of options, and foster quality and innovation? We believe that the market – free choice among parents and schools having the ability to operate as they see best – has proven over and over again in a variety of industries to have better outcomes than Mike Petrilli sitting in an office deciding what quality is… as opposed to what individual parents think [quality] is.

Harris then responded by claiming that I was saying the evidence was “irrelevant,” to which I replied:

It’s irrelevent in terms of how we should design the policy, in terms of whether we should kick [schools] out or not, but I think it’s very important that we know how well these programs are working. Test scores do measure something. They are important. They’re not everything, but I think they’re a pretty decent proxy for quality…

In other words, yes, test scores matter. But they are far from the only things that matter. Test scores should be one of many factors that inform parents so that they can make the final decision about what’s best for their children, rather than having the government eliminate what might well be their least bad option based on a single performance measure.

I am grateful that Dr. Harris took the time both to attend our policy forum and to continue the debate on his blog afterward. I look forward to continued dialogue regarding our shared goal of expanding educational opportunity for all children.

(Cross-posted at Cato-at-Liberty.)

Posted by Jay P. Greene

Posted by Jay P. Greene