(Guest post by Greg Forster)

Deserve the Al Copeland Award? John Lasseter practically is the Al Copeland Award.

Improve the human condition? This man has not only reinvented movie animation technology, not to mention Hollywood’s business model. He has proven the superior power of the transcendent – the good, the true and the beautiful – in the marketplace of culture. He beat the purveyors of schlock, and he did it in the only way that really counts – by putting more asses in seats than they could. He didn’t defeat the schlockmeisters by shaming them, but by selling so many tickets that he ran them out of the marketplace. He proved that edifying culture can sell, which is another way of saying it can survive and sustain itself. He and the circle of people clustered around him are almost the only people left in Hollywood who know how to tell an edifying story, and they are literally the only people left who can tell an edifying story that appeals to everyone across all our cultural boundaries.

As I recently argued at some length, they are in the process of saving American civilization.

Courtesy of the Onion

There are basically two kinds of Al winners – inventor/entrepreneurs and champions of unpopular causes. They’re either David going up against Goliath, or they’re Elijah calling down fire on the lonely altar. Lasseter is both.

Inventor/entrepreneur? Lasseter dreamed for all his boyhood of working for Disney, and by some miracle he got himself chained to a drafting table deep in the bowels of the Disney dungeon, slaving away as the tenth assistant drawer of left pinkies . . . and then promptly got himself fired from his dream job for taking an interest in computer animation just at a moment when (unbeknownst to him) one of his superiors had decided the future lay elsewhere.

Perhaps because computers would eliminate people like him and elevate people like Lasseter? Can’t have that! Just like any good Al winner, John Lasseter saw the future, and he didn’t care whose cushy job was threatened by it.

So, cast out of the only company he ever wanted to work for, Lasseter chased down the future and seized it by the throat, and made it sing so loud and so beautifully that twenty years later, Disney came crawling back to him and begged him not just to come back, but to take over all their animated movie making, oversee design of all their theme park rides, and direct a good chunk of their other stuff to boot.

Mr. Incredible, second from the right, poses with some less impressive heroes

Now, all that would be Al-worthy if Lasseter’s innovations were merely technical. And it is hard, now, to remember that back in 1995 the thing that everyone thought was revolutionary about Toy Story was the technology.

But Lasseter’s innovation is as much the way his movie studio runs. He has figured out how to run a team of creative people in such a way that it not only produces material that is simultaneously artisitcally and commercially successful, but does so with sufficient regularity and reliability that you can pitch it to investors. He has taken the Muses to the bank.

And they really are the Muses. Lasseter and his people are not just “artistically and commercially successful.” They are bringing the transcendent things – the good, the true and the beautiful – back into the center of American culture.

Lasseter is as much a deserving Al winner as the champion of unpopular causes as he is so as an inventor/entrepreneur.

And what causes they are! If some have won the Al by standing up for this or that cause which is unpopular, but is nonetheless one of the keys to maintaining our justice, virtue and freedom as a people, Lasseter has stood up for just about all of the causes that are unpopular, but necessary for our justice, virtue and freedom:

- Do not make your own happiness the aim of your life (Inside Out)

- Love means putting other people’s needs ahead of yours (Frozen)

- Accept your mortality (Toy Story 2)

- Honor the superiority of exceptional talent (The Incredibles)

- Manhood involves fatherhood (UP)

- Womanhood involves motherhood (Brave)

- Let your children take risks and grow up (Finding Nemo)

- Don’t envy your brother (Toy Story)

- Legitimate government rests on justice and popular consent (Toy Story 3)

- Those who live for nothing but pleasure are fit for nothing but slavery (WALL-E)

- Work your ass off, and be content with a family and your daily bread (Princess and the Frog)

- Beauty transcends both nature and custom (Ratatouille)

- Technology is for solving problems, not imposing your will on others (Big Hero 6)

No one else teaches these things and is listened to receptively by all sectors of society. Without this man, what hope would there be for these values in the long term? No, seriously, tell me. I’ll wait.

Two more Al-worthy accomplishments:

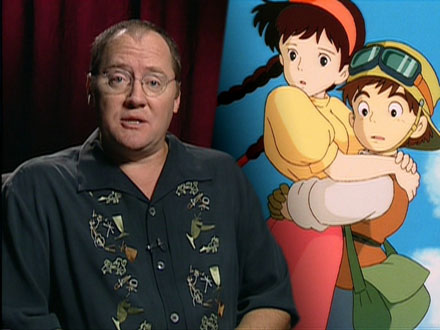

Lasseter is almost single-handedly responsible for the English language translation of the beautiful works of Hayao Miyazaki, who was practically unknown over here until Lasseter introduced us to him.

And Lasseter would be, if he won, the first Al winner to outdo the award’s illustrious namesake in tasteful shirts.

Lasseter owns over 1,000 Hawaiian shirts and wears one every day.

You can’t ask for a clearer avatar of the Spirit of Al Copeland!

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster