(Guest post by Greg Forster)

For a while now I’ve anticipated that the next installment of this series would be about power. Since Jay has broached the subject, I guess it’s finally time to get around to writing what I’ve been planning!

A quick review of my Unified Field Theorem of Education Reform:

Part 1: Education reformers shake out into two groups, which I call the “liberal artists” and the “pragmatists.” The liberal artists want to teach first the three Rs, then traditional “academic” content more generally. Their strength is their insistence on tangible accountability for teaching all children; their weakness is their overreliance on standardized testing – now culminating in the current effort to create a government-controlled national testing regime which logically implies the further step of imposing a single curriculum on all schools under the control of a central authority. The pragmatists want to make education in various ways “more relevant to real life.” Their strength is their desire to create new models of education that will prepare students better for life in the (changing) world. Their weakness is their tendency to discount (in practice if not in rhetoric) the value of traditional academics, and especially their fear of accountability systems.

Part 2: Both sides undermine not only education governance (the focus in Part 1) but pedagogy as well. The pragmatists want to abstract “skills” from “content” and focus on teaching the skills; they fail to appreciate that the only way to learn skills is by leaning content. You can never teach “skills” directly. The liberal artists want to abstract “knowledge” from “practice” and focus on teaching the knowledge; they fail to appreciate that all the really important knowledge is intricately bound up with practice, and can only be learned practically.

Part 3: Liberal artists need to get over their testaphilia, and pragmatists need to get over their testaphobia. A vast quantity of what students deperately need to learn must be learned in ways that can’t be tested with the level of objective systematization the liberal artists insist upon. You can “test” practical knowledge but not in the ways the liberal artists want – and not in ways that can be effectively used as the basis of an accountability regime. Yet standardized testing, and more generally the “rote” “regurgitation” of “mere” “facts,” is always going to be a crucial part of good education. In Daniel Willingham’s language, you can’t get to the “deep structure” of problems, which is what the pragmatists want, until you’ve first mastered the “surface structure,” which is the rote facts the pragmatists disdain. You have to walk before you can fly.

Running through all this is the tension between governance and pedagogy. Once we decide what we want schools to do, how do we structure the system to try to get them to do that?

The links beteween each camp’s pedagogy and governance, both in their good and bad aspects, run much deeper than it may at first appear. What’s really at stake is our view of the human person.

An analogy to politics will help here. In modern political philosophy there are basically three anthroplogies on offer. They give rise to different political systems.

- You can be cynical about human nature, thinking that people are basically bad. This leads more or less directly to an explicitly authoritarian, implicitly totalitarian tyranny of “enlightened” despots. Because people are basically bad, no one can ever have legitimate power (no one deserves it) and the world will really operate by illegitimate power no matter what you do. So you might as well give the power to the smartest people so they will at least make things run more smoothly and everyone will have an easier time of it. Machiavelli and Hobbes fit this model.

- You can be naive about human nature, thinking that people are basically good. This also leads more or less directly to an explicitly authoritarian, implicitly totalitarian tyranny of “enlightened” despots. Because people are good, they will naturally want to cooperate to make everyone better off, which of course means putting things under the control of the smartest, best people. And those people ought to have the power to coerce everyone’s cooperation, becasue such power won’t really need to be exercised very much – just enough to encourage people to get over their less powerful selfish tendencies and live into their natural desire to benefit others, which is (underneath the superficial layer of selfishness) really their deeper and stronger desire. The payoff from giving dictatorial power to experts is huge (because the experts are not only smart but good and trustworthy) and the cost is small (because the power won’t have to be exercised much). Rousseau and Hegel fit this model.

- You can take a mixed view of human nature, thinking that people are both basically good and basically bad. They need freedom to do their good stuff, but also enough restraint to keep them from getting out of line and destroying other people’s good stuff; the rulers, in turn, must be strong enough to restrain violence, but not so strong that they themselves become unaccountable. This is the anthropology of liberal democracy, freedom of religion, and the entrepreneurial economy; Locke, Montesquieu and Madison are its architechts.

The thing to note is that societies cannot be counted on to remain faithful to one model. In particular, the mixed model on which liberal democracy, freedom of religion and entrepreneurial economy are built is really darned difficult to maintain. We are constantly falling away into cynicism on the one side (e.g. Cass Sunstein, Catherine MacKinnon, Saul Alinsky) or naivete on the other (e.g. Michael Lerner, Alan Wolfe, Jim Wallis) with the same disastrous consequences every time.

How does this relate to pedagogy and governance in education? I propose that education needs to be based on a mixed model, but is constantly falling away into one or the other of two truncated models – and that’s why substantive education issues are constantly being hijacked by brute political power.

Look at the liberal artists. How did we get to a point where the people dedicated to the full flowering of human knowledge represented by “traditional academics” are in the process of reducing the content of education to what can be measured by bubble tests – and lining up to create a national dictator that will reach into every school in America and crush everything that isn’t bubble tests?

It’s because their anthropology privileges intellect over action. A human being is a mind that has a body. What they want is to educate the mind. The body is really of no concern to them. Even the mind is only of interest insofar as it knows things – the mind’s ability to do things through the body is not interesting. Re-reading my first post in this series, this is really clear in the exchange between Jay and Checker about whether schools should teach things like “entrepreneurial attitudes.”

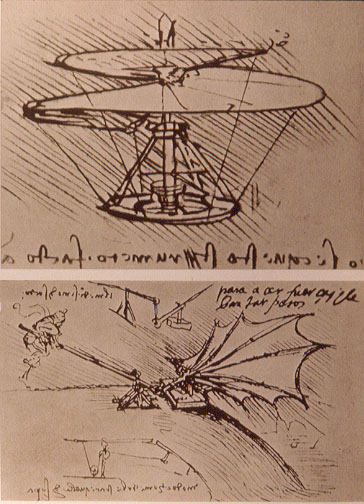

Checker Finn’s ideal school

This anthropology implies an aristocracy of intellect. The system should serve the interests of those who are capable of learning. The liberal artists think they’re egalitarians and democratizers because they stick up for the poor black kids who want to learn – and, as I have said over and over, they’ve done us a great service. They have indeed been the great titanic warriors against race and class aristocracies. But there are other kinds of aristocracies as well. The liberal artists only stick up for the kids who want to learn in a certain way: the intellectual way, the bubble test way. They want the whole system to serve only the kids who desire to know for knowledge’s sake – and that’s not most kids. What about the kids who want to invent new things, or acheive greatness in other ways, and who might be willing to learn academics as a stepping stone to that but not for its own sake? They’re chucked into the maw of the intellectual tyranny.

Ken Robinson was wrong (in that video back in Part 1) to attribute this anthropology to the Enlightenment; it is actually far older, and has historically been associated with undemocratic power structures. Mind/body dualism was the philosophy of Greco-Roman aristocracy – Athens was the only democracy of any importance in the ancient world, and it executed the great dualist Socrates. Even during the Enlightenment, those who strongly embraced mind/body dualism (like Descartes) were strong supporters of traditional power structures. It was those who challenged mind/body dualism, like Locke, who ushered in democracy.

What about the pragmatists? It’s tempting to say that they have the opposite problem – they think kids are bodies that have minds. But that’s actually wrong. The strength of the pragmatists is that they’re not plagued by mind/body dualism.

Their problem is egalitarianism. They don’t want education to result in inequalities – no inequalities of life outcomes, but more fundamentally, no inequalities of educational outcomes. To draw a distinction, even in thought, between those who can accomplish more and those who can accomplish less is itself wrong. Anything that tends to reinforce the appearance of such distinctions, or (worse) explicitly assume such distinctions and build on them, is in principle radically evil.

This explains their testaphobia and their general aversion to accountability systems. It also explains why they are de facto but not de jure hostile to traditional academics. They have no objection to academics in principle – provided the illusion of equal outcomes is not punctured. But, of course, it always is. Much safer to stick to content-free, purely “practical” projects that teach “skills.”

The picture offered to us is one of glorious diversity in which every child is radically different, and none of the differences matter.

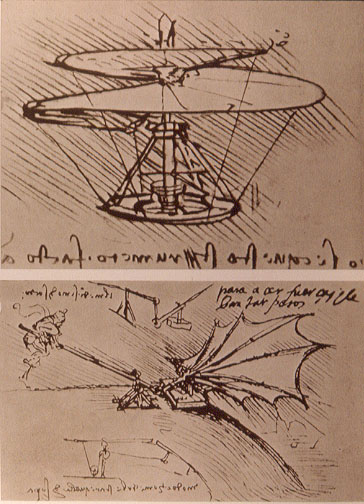

“You can think for yourselves!”

“Yes! We can think for ourselves!”

“You are all individuals!”

“Yes! We are all individuals!”

Naturally, while the liberal artists are striving to build an aristocracy, the pragmatists are striving to build a tyranny of the majority – the mob rule of unlimited democracy. This was their original sin going all the way back to John Dewey, whose perfidy begins right at the beginning when he sets out to redesign the whole educational enterprise to produce, not the fullest possible flourishing of human capacities, but people suited to fit the new, radical political system that early 20th century progressives were working so hard to build. Human beings are little clay figures just waiting for Dewey and his acolytes to mold them into the politically convenient shape. All the worst aspects of educational pragmatism can really be traced back to this original politicization of the project.

So both camps find substantial resistance to their desires – the liberal artists, in children who are capable of achievement but don’t highly value knowledge for its own sake; the pragmatists, in children who are capable of excellence (even the kinds of excellence pragmatists claim to value) and need special nurturing to achieve it.

And both camps, their vision cramped by narrow anthropologies, fail to see the legitimacy of this resistance. To them, the resistance appears to be simply obscurantism. Hence they feel perfectly justified stamping it out by force.

And naturally, when they seek power, they both reach for the strongest of all social weapons in modern culture – science.

Say that you favor a given approach – in education, in politics, in culture – because it is best suited to the nature of the human person, or because it best embodies the principles and historic self-understanding of the American people, and you will struggle even to get a hearing. But if you say that “the science” supports your view, the world will fall at your feet.

Of course, this means powerful interest groups rush in to seize hold of “science,” to trumpet whatever suits their preferences, downplay its limitations, and delegitimize any contrary evidence. If they succeed – which they don’t always, but they do often enough – “the science” quickly ceasees to be science at all. That’s why “scientific” tyrannies like the Soviet Union had to put so many real scientists in jail – or in the ground.

This was, again, the original sin of Dewey and the whole “pragmatist” movement in early 20th century philosophy. The goal of that school was to undermine the philosophical structure of knowledge on which real science depends, so that they would then have a free hand to bend “science” to their will. I believe it was George Orwell who said that philosophical pragmatism amounts to saying that truth is determined by who has more guns.

But the liberal artists are no longer very much better. They didn’t used to flatten their understanding of a good education down to the level that could be measured “scientifically” on tests. But the imperative to seek power and crush resistance has driven them to that point.

How, then, do we escape from both aristocracy and mobocracy, and undo the tyranny of science? Stay tuned.

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster