(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

The Arizona School Boards Association had their annual law conference last week, and had William Mathis from the Think Tank Review Project present on “Are Things as Sunny as They Seem in Florida?”

I went first, and presented charts like this, showing the vast improvement in Florida’s 3rd grade reading scores:

I have repeatedly asked the Think Tank Review Project people to explain why Florida’s 4th Grade NAEP scores continued to rise in 2007 and 2009 even as 3rd grade retention fell substantially. Or for that matter, why their 3rd grade scores have improved so strongly. Dr. Mathis made no attempt to address the issue.

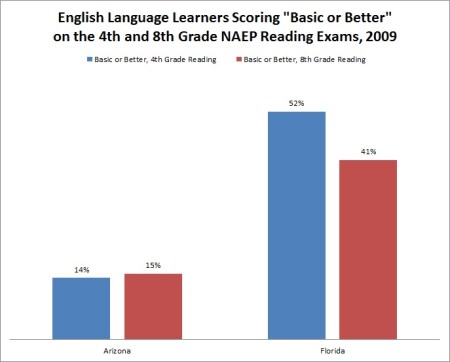

I also presented charts like these:

Now, call me crazy, but when you are the state called “Arizona” in above chart, you might want to make a careful study of what the other state did to get their English Language Learners to read. This phenomenon of course is not limited to ELL. Another chart I used showed the combined learning gains on all four NAEP tests for children with disabilities for the entire period we have data from all 50 states (2003-2009).

Just in case you are squinting that’s Florida in red with a gain of 69 points and Arizona in green with a decline of two points.

Dr. Mathis proceeded with his presentation unperturbed. He complained about the 3rd grade retention policy without any effort to explain why Florida’s 3rd grade scores had so profoundly improved, and why Florida’s 4th grade NAEP scores continue to increase even as retention rates have significantly declined.

To give Dr. Mathis’ presentation the fairest possible reading, I would say that he was trying to make the following points: that correlation is not causation, and that to use the terminology of Campbell and Stanley, I had not “controlled for history.” That is to say, there could be other possible explanations for Florida’s gains other than the reforms.

Now it is of course the case that correlation can lead us very much astray, and it is the case that “history” has a nasty habit of bedevilling our theories of causality. As I have noted in the past, however, the Florida reforms unfolded in the real world, rather than in a random assignment study. A great many things unfolded all at once. This is called “life” and there is nothing to be done about this but to gather as much data as possible to draw the best informed decisions we can.

Both Chatteriji and Mathis ignored the Education Next piece in which Dan Lips and I examined other possible explanations for Florida’s gains. Huge spending increases (nope), decline in the percentage of low-income or minority students (nope-increases in both), preschool voucher program (nope- students too young to have aged into the NAEP sample) and class size amendment (nope- implemented very slowly, gains already well under way, formal evaluations negative) and retention law (scores continued to rise even as retention fell). This sort of information might be unhelpful if you are simply trying to get the idea in that something other than a set of hated reforms drove the gains.

Mathis however posited other types of “history” and noted other ways that the world had changed after 1998. On his list of other parts of uncontrolled “history” with regards to Florida’s gains were Harry Potter books (kids reading more fiction) and the more widespread availability of personal computers at home.

Sadly, the format of the panel did not provide time for rebuttal. We had two other people on with us, and took questions from the audience. Had there been such time, however, I would have noted that while Arizona may seem backwards to outsiders (Dr. Mathis lives in Colorado) that we do in fact have Harry Potter books and even personal computers in our humble little patch of cactus. In fact, I am rather confident that Harry Potter books and personal computers became increasingly pervasive in all 50 states.

You never know, Harry Potter books could have powerful educational properties that only manifest themselves on massive peninsulas with high rates of humidity and large concentrations of alligators. The children of Arizona, landlocked in an arid climate, and with not much more in the large lizard department than the occasional Gila monster, may have been left behind. I can’t prove that this isn’t the cause after all.

Nevertheless I’m going to stick with my theory that Governor Bush’s success in implementing a varied and comprehensive set of K-12 reforms in 1999 served as the driver for the large increases in academic attainment seen in Florida’s NAEP scores since 1998. Dr. Mathis and his compatriots can continue to play their stategic nihlism game if they wish, ignoring the problems with their arguments and the studies most on point for the subject at hand (like the regression discontinuity studies of Florida’s retention policy).

Until they put forward a plausible explanation for Florida’s gains, I cannot for the life of me find any reason to take them seriously.

Posted by matthewladner

Posted by matthewladner  (Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)