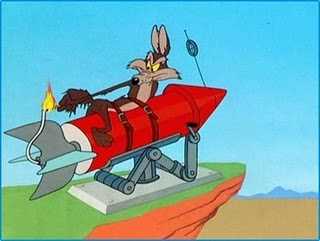

Vaclav Klaus and Vaclav Havel

(Guest post by Greg Forster)

Jay is causing quite a stir with his two-part deconstruction of the Gates Foundation. To those who may be upset, let me say the following two things.

First: Jay’s posts will have no important impact – unless they’re true.

Second: That fact itself demonstrates why the Gates command-and-control approach to education reform is bound to fail.

As Jay points out in his two posts, the Gates effort has undermined the intellectual integrity of many people associated with it. Why? The immediate answer is simple. The Gates strategy is a power agenda. And as Jay and I have both had occasion to point out, power agendas seek to subvert “science” in order to create the impression that their policies are scientifically supported. Other knowledge systems are equally vulnerable, but in our society “science” is the only knowledge system whose validity and importance is recognized by virtually everyone; hence science is the key target for corruption.

Don’t get me wrong; power, considered simply by itself, is good. It’s better to have it than not have it. You can’t get much good done without it. But all good things come with natural temptations and dangers, and one of the natural temptations and dangers that always – always – comes with power is the constant threat to subvert knowledge.

I don’t know their hearts, but I’ll bet the Gates people are not bad people, as people go. They just aren’t awake to, and taking steps to check, this natural danger. They’re not aware of what they’re doing and don’t recognize the process of intellectual corruption for what it is even when it’s held up to their faces – because that failure of recognition is itself the natural attendant danger of power.

But this just leads us to a deeper question. Why do power agendas always display this tendency to corrupt knowledge systems? Why does Gates invest hundreds of millions of dollars in research when it’s clear they already know what they want to be true and aren’t interested in following the evidence? And why does it spend hundreds of millions more subverting the individuals and organizations who talk about education research? Why does Gates care what a bunch of bloggers think? What explains this enormous investment?

Because truth has a power of its own. People want to believe what’s true. Even wicked people who deliberately decieve others for the sake of power would not be willing to be decieved themselves for the sake of power. Every human being has a desire to know truth and live in accordance with that knowledge. To be sure, other desires compete with this desire and often win out over it. But the desire is always there and can always be harnessed as a force for social change – that is, for power. So the people who care about power always have to worry about the people who care about truth.

This dynamic is as old as time. From Plato to Paul, from Martin Luther to Martin Luther King, people who care about truth more than they care about power have been a threat to those who care more about power than they do about truth.

And the reverse is also true, as can be surmised from the response of the powerful to the four people I’ve just named. Asked what he would do to help win support from the pope for the Russian war effort against Germany, Stalin snorted, “The pope? How many divisions has he got?” In a more reflective hour, however, he spoke with more shrewdness: “Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas?”

Mind you, though, the trouble is not entirely on the side of the “power people.” We “truth people” have our own, equally dangerous dysfunctions. We know that the social systems of power are a threat to the social systems of knowledge production, so our natural instinct in many cases is to fear power. We build high ivory towers and steer clear of the world of power. And by doing so we render ourselves not only irrelevant and irresponsible, but even irrational – because our isolation from “the real world” leaves us extremely vulnerable to falling for spurious ideologies that flatter our prejudices.

For example.

The natural and intrinsic dangers of the life devoted to truth are themselves just as much a threat to the process of knowledge production as the natural and intrinsic dangers of the life devoted to power.

In spite of the natural rivalry between truth and power, or perhaps because of it, people who have gone all the way to the two extremes – those who care only about power and those who care only about truth – often make alliance with one another. The power people provide subsidies that allow the truth people to spend all day in their offices thinking, computing, writing, talking, and doing everything they like to do; in exchange, the truth people anoint the power people as legitimate. Everyone gets what he wants – except for the other 99% of us, who get screwed.

The answer to this dilemma, of course, is that we have to care about both truth and power. Not to care about truth is dishonest. Not to care about power is irresponsible. Both are self-destructive. (Not to mention other-destructive!)

In reality, however, human beings are rarely so balanced. All virtues come in matched pairs of opposites (e.g. courage and moderation, candor and tact) and each person tends to care more about one necessary virtue than its opposite. That’s why people need social systems in which the legitimacy of opposing virtues is respected and processed in a way that doesn’t subordinate the one to the other.

As a little vignette to illustrate this, consider the roles played by Vaclav Havel and Vaclav Klaus in Czech liberation. Under the Czechoslovak tyranny, Havel lived underground, writing tracts and plays and organizing a network of dissident intellectuals. He had no use for the regime’s systems of power, except as targets – and slow, fat targets they were for a powerful genius like his. Havel’s greatest non-fiction work may be his book-length essay “The Power of the Powerless,” in which he argues that truth is the power of the powerless because all people desire ” to live in the truth.” Unchecked power forces people to live a lie, and the more they have to live a lie the stronger the desire to live in the truth grows. When that desire grows stronger than the desire to live quietly, the power of the powerless becomes greater than the power of the powerful.

In 1989, Havel’s circle of dissidents triggered the crisis that brought down the regime. Protestors gathered in Wenceslas Square for days, then weeks, in defiance of machine-gun toting thugs who might gun them all down at any moment. Havel addressed the crowd daily, and was in little danger because wherever he went, throngs of ordinary people spontaneously surrounded him in an effort to shield him from snipers. “You have to kill us all” was the implicit message of the protestors – and the regime broke. Havel’s game plan, Havel’s leadership, Havel’s hour.

Klaus, on the other hand, was an economist for the state bank under the Czechosolvak tyranny. He was not a supporter of the regime, but he apparently saw nothing inconsistent between that and a banking career within the system. He joined the resistance movement early during the revolution of 1989, and before long he drew a large following of support backing him as a leader – two facts that indicate, I think, that he had legitimacy as a reformer.

Havel and his circle, however, couldn’t stand him. More important, they didn’t trust him. They still don’t. To this day, Klaus is dogged by whispers about all the nasty things he must have been doing to keep his position in the state bank, while people like Havel were going to jail for the sake of truth. And it’s not like there’s not some reasonableness to that disposition.

But the bottom line was that Havel didn’t know how to run a country, and Klaus did. In 1989-1991 those two facts rapidly became clear to a large number of people. Havel and his circle had founded Civic Forum as an umbrella party for the resistance movement, and after the regime collapsed it was the “national unity party” under which the new democracy was governed. A year after the revolution, to the surprise and disgust of the Havel circle, the national party deputies elected Klaus to chair the party. Before long an anti-Klaus faction walked out of the party and founded a new one, completing the transition to a system of electoral party competition. Havel, as president of the new nation, stood formally apart from these events, but everyone knew where his sympathies lay.

With the separation of the Czech Republic from Slovakia in 1992, Klaus became its prime minister. From then until Havel’s retirement in 2003, Klaus ran the government and Havel served as head of state. And a bang-up job they both did of it, too – Klaus’ political, economic and administrative leadership brought about a peaceful and successful transition from state ownership and command-and-control to prosperity and personal freedom, while Havel articulated for his nation a renewed understanding of the political community that grounded it in the humane and civil virtues of freedom and personal responsibility. Neither of those feats could have succeeded without the other.

Havel (truth) and Klaus (power) naturally dislike and distrust each other. But the Czech resistance after 1989 and the Czech government in the two succeeding decades made room for them both – Klaus became president after Havel’s retirement from office, while Havel has continued to write and speak. As a result, the Velvet Revolution and the subsequent history of the Czech Republic stand as miraculous modern models of peace, prosperity, order and justice.

So what would an education policy that took seriously both truth and power look like? Stay tuned for Part II.

(You can tell I’m smarter than Jay because I use Roman numerals for my serialized posts.)

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)