(Guest post by Greg Forster)

Wow, the graphic above seems to have struck a sensitive spot with our Sith apprentice, Leo Casey. Here’s his surprisingly defensive overreaction.

Leo thinks he has my motives all figured out. He thinks my post last week was trying to sow division within the union by pitting their internal constituencies against one another.

Er, no. I don’t think many UFT members read Jay P. Greene’s Blog, except the ones who are paid to.

Leo’s evidence about my motives consists entirely of a passage from a book written 20 years ago by people who have no connection to me. Oh, and he lists my affiliation as being with “the Milton Friedman Foundational Educational Choice.” Two words right out of five ain’t bad – at least by his standards.

You would think that a person who has been caught participating in eggregious political fraud and promoting scandalous calumny would be more careful. Or maybe you wouldn’t.

Sherman Dorn likewise misconstrues my purpose (although without the foot-shooting intellectual slapstick we’ve come to expect from Leo). Dorn writes of my post: “This is corruption! is the implication.”

Er, no. I not only didn’t say anything about corruption, I didn’t imply anything about it. There’s nothing corrupt about UFT representing more non-teachers than actual teachers.

Dorn invokes my status as a political scientist with hoity-toity academic credentials in order to sadly lament that I failed to provide an extensive discussion of the academic literature on different types of voting systems in my blog post. Well, let’s try to satisfy him by adopting some unnecessarily opaque academic jargon as we look back at the actual, clearly and explicitly expressed purpose of the post.

My post is what political scientists call “positive theory.” That is, I’m offering an explanatory model of the unions’ behavior. Why do unions invest so much of their effort in racking up a trillion dollars in mostly-unfunded pension obligations, rather than taking a more evenhanded (and thus presumably less noticeable) approach to what kinds of swag they grab? Why do they support policies that make working conditions worse for teachers?

Down here in the dark bowls of the earth where we “trolls” live, the prevailing explanation is that the union leadership has incentives to do things that fatten themselves at the expense of the union membership. Well, I’m not saying that’s not true! But there’s at least one other plausible theory, and my post offered it. Or both could be right!

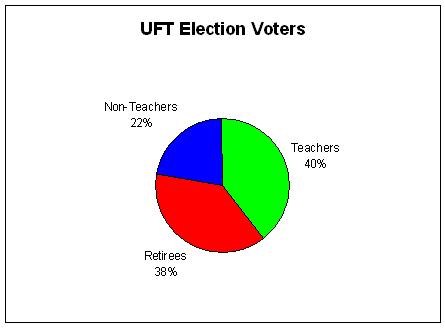

But . . . I’ll admit that I did have a hidden agenda! Namely, I wanted to create some transparency about whether the UFT represents “teachers.” It’s not wrong for UFT to represent more non-teachers than it does teachers, but it’s wrong for UFT to puff itself up as The Voice of The Teacher in order to promote policies that serve another agenda. Not that I think a union should puff itself up as The Voice of the Teacher even if it does primarily represent teachers, any more than I think the National Organization for Women should puff itself up as The Voice of Women. But how much more shameless would it be if most voting members of NOW were men?

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster