(Guest post by Greg Forster)

After my two initial Pass the Popcorn entries on The Dark Knight, outlining what I thought was the main theme of the movie, I decided to let that go for a while rather than harp on it after I had already said my piece. But I always knew that after I had spent a while meandering around other topics, I would circle back around to the heart of the movie – the moral hypocrisy of all human beings and all civilization.

In the interim, the death of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has provided a reminder of just how perennially true and relevant the movie’s observations are. If any man of our time was ever entitled to treat his enemies as simply evil and his own side as simply good, surely that man was Solzhenitsyn. But, to the contrary, he made a point of not losing sight of the real basis of evil in the moral corruption that is endemic to our species, and that is one of the reasons his intellectual legacy will live on well beyond the context of the particular historical conflict in which he participated. To say it again, if any man was entitled to treat some people as “basically good” and other people as “basically bad,” he was – but the whole point is that no man is in fact entitled to do so.

Solzhenitsyn expressed the key insight succinctly yet beautifully:

“The line between good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart.”

I anticipate (without ruling anything out) that this will be my last PTP entry on The Dark Knight, at least for a good while. I’d like to end where the movie ended.

To recap the central point of my first post quickly: All human beings are both good and evil, but it isn’t in their nature to admit this about themselves; hence the ubiquitous fiction that “people are basically good.” People tell themselves this ultimately because it allows them to avert their gaze from their own corruption. The outcome of this is the outrageous extreme of moral hypocrisy that is easily observable (provided we’re willing to look without flinching) both in every individual person (no exceptions) and in society as a whole. In this movie, we see it play out on the individual level with the Joker’s desire to induce Batman to kill him, and at the social level with the fact that the whole restoration of Gotham City rests on the reputation of Harvey Dent – because people need heroes. Why do people need heroes? Because they’re not “basically good.” If people were basically good they wouldn’t make their support for civic justice conditional on the moral purity of some fallen human being. The very fact that people need to be rallied to support justice shows how far from real righteousness they are.

The Joker has our number:

“When the chips are down, these . . . these ‘civilized people’ . . . they’ll eat each other.”

So did Harvey Dent, in his way:

“You either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”

One thing I didn’t comment on earlier is what Gordon says at Dent’s funeral. I noticed it especially the second time I saw the movie. If memory serves, Gordon says of Dent that “he was the hero we deserved – no more.” No more? Shouldn’t that be no less? Or is Gordon slyly reaching out to the few people in Gotham who know the truth, reassuring them that at least somebody realizes what’s really going on – that Dent was the hero Gotham deserved in the sense that Gotham deserved a man who really, really wanted to be good but ultimately failed to live up to his own standards, because that’s exactly how Gotham itself behaved?

As I wrote before, one of this movie’s biggest strengths is that it doesn’t attempt to convince us that it’s a good thing that people need hypocrisy. It’s a bad thing – it’s a sign of how evil we are – that people need hypocrisy.

But since people do in fact need it, it may not be wrong to supply it.

That last assertion is the thought the movie ends on, and it’s where I stopped my first post, saying “hold that thought.” Well, I’ve been holding that thought for a month and a half now. It’s time to unpack it.

Is it wrong to supply hypocrisy? We might answer by saying that if it is, we’re all totally screwed. On the evidence, it appears that no civil order of any kind can long survive without falling back on collossal heaps of hypocrisy.

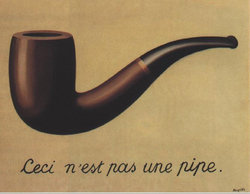

I’m not even talking about the kind of rank everyday hypocrisy that hits you in the face every time you pick up a newspaper. Although there’s always plenty of that – obviously. Take the frenzy over the past month against “speculators” who have, according to both presidential candidates and most of our other leaders, driven up the price of gas. It’s an old social science maxim that you should never posit malice if ignorance covers the facts, but can John McCain and Barack Obama and all the rest of them really be as ignorant as all that? As Chrales Krauthammer wrote recently: “Congressional Democrats demand . . . a clampdown on ‘speculators.’ The Democrats proposed this a month ago. In the meantime, ‘speculators’ have driven the price down by $25 a barrel. Still want to stop them? In what universe do traders only bet on the price going up?”

It beggars belief that our leaders don’t know exactly what they’re shoveling here. And this is just one issue out of hundreds where the same dynamic occurs. Is there a single political issue where the public discourse isn’t dominated by claims that can’t possibly be believed by those who make them? Not for nothing did Michael Kinsley define a “gaffe” as when a politician accidentally tells the truth. But Mickey Kaus strikes nearer to the mark when he says that Kinsley’s definition ought to be expanded to include all cases where a politician accidentally says what he really thinks, whether true or not.

But that kind of hypocrisy doesn’t go to the roots of social order. Although its omnipresence would be sufficient to prove the universality of some type of corruption in human nature, from a standpoint of the political system it’s an epiphenomenon.

The real hypocrisy runs deeper. It was well captured a while back by an old college acquaintence of mine who subsequently served for a while as a small-town prosecutor. Please read this brutally honest essay in which he reflects, after having left the job, on the nature of his service representing the people in our courts:

We who deal in the laws of a free people are puppeteers. We must be so . . . because our system works better than any other, and because we have no choice but to make it work. We have to give the appearance that we possess the wisdom and authority needed to make our society function. We have to make believe that our culture possesses an exclamation point as strong and as firm as the question mark of [classical] liberalism. So on with the courtroom pomp and ceremony, on with the bluster and posturing! . . .

Men who doubt themselves need puppet shows. They need little passion plays to affirm the dignity of a frequently silly and corrupt form of governance, lest something more dignified but less humane rise to power. Ours is a system of laws administered by flawed and small-souled lawyers to foolish and wicked men; such a system cannot survive without the pantomimes of solemnity.

And note that he has (as far as I can tell) no regrets about having chosen to serve in this capacity. As he says, our system is better than the alternatives (i.e. “something more dignified but less humane”) and given the realities of fallen human psychology this is what it takes to sustain it.

It was with this in mind that I chose the title “City of the Dark Knight” for my mini-series on this movie. The title is meant as a tribute (an obscure one, no doubt) to Augustine, whose political theory I was reminded of by The Dark Knight’s unflinching meditation on society’s hypocrisy. Augustine works so hard to puncture the Romans’ ridiculous charade of virtue and honor not because he hates them – he loves Rome dearly – but because penetrating the mask of society’s pretense of righteousness is for him (as it was for Plato) the first step to any serious wisdom about justice. The fundamental political reality is that people are neither “basically good” or “basically bad.” We tend to associate the observation that if people were “basically good” there would be no government with Madison’s Federalist #10, but I think (though I’m open to argument) that Augustine is the real source of the insight. And there would equally be no government if people were “basically bad,” since people with no natural idea of justice would never develop a system for enforcing justice (however intellectually impressive Hobbes’s attempt to argue the contrary may be). Though Augustine doesn’t put it in exactly these words (or not that I recall), I think we can say that for him politics is a manifestation of the ongoing tension between the image of God that was planted in all men at creation and the moral corruption that was planted in all men at the fall.

And this, if I may be autobiographical for a moment, is why I fled screaming from Washington after spending a year between college and grad school working there. When people with little experience of academia hear that I have a Ph.D. in political science, about 50% of the time they immediately ask me “so are you going to run for president?” Set aside for a moment the charming naivete that associates the pursuit of a Ph.D. in political science with ambition to public service. More to the point is the fact that I could never serve in public office because I couldn’t practice the hypocrisy that all public servants, seemingly without exception, must practice on a regular basis to do their jobs.

Yet though I am not the man to do it, I can see clearly the necessity of maintaining the hypocrisy. Classically, “prudence” was identified as one of the four cardinal virtues. We have a moral responsibility to consider the outcomes of our choices and act so that we aim for those outcomes to conform to the proper ordering of ends (i.e. goals or purposes). Can it really be our responsibility to rank candor above the preservation of humanity? For a long time I was spellbound by Kant’s iron declaration “let justice be done though the heavens fall.” It would be a worthy resolution if “justice” meant simply “goodness” or “righteousness,” that is, virtue as such – including prudence. But “justice” is not virtue as such, it is only one of the virtues. And as Aristotle observed, only virtue as such can be pursued without limit. You can’t go “too far” in the right direction. But any partial good, as opposed to good as such, can be pursued too far – that is, to the exclusion of other partial goods that ought not to be excluded. Hence Kant was actually driven to the insane extreme of preferring the destruction of the universe to the utterance of a single false statement.

The healthy conscience recoils from Kant’s famous statement that if a man intending to murder your friend asks whether your friend is home, and he is, you should tell the truth. (For a while I wondered whether this claim was misunderstood – in the 18th century, gentlemen were usually armed, so when Kant said that you shouldn’t compromise your honor by lying, was he assuming that you would just shoot the guy instead? But when I shared this speculation with a friend, he pointed out that while gentlemen in 18th century England were usually armed, that wouldn’t have been the case in 18th century Prussia.)

And Kant’s dilemma of whether to lie to the murderer is, ultimately, the choice Batman and Gordon must make at the end of the movie. The “murderer” in this scenario is Gotham City itself – which threatens to give up on its own salvation unless it is told the lie that Batman and Gordon choose to tell it.

With that, I’ve said my piece. (Again.) Next week, on to other movies.

UPDATE: Well, I hadn’t quite said my whole piece. See here for the next chapter.

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster