Surely we can find a happy medium?

(Guest post by Greg Forster)

I’ve just read a fascinating article – Frederick Herzberg’s “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” from the Harvard Business Review. The 1987 version, an update of the original 1968 article of the same title, went on to become HBR’s most requested reprint ever.

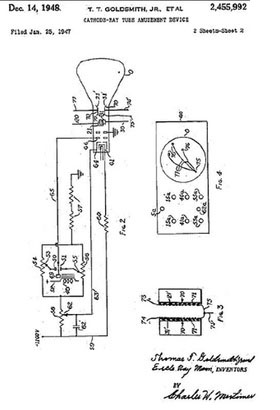

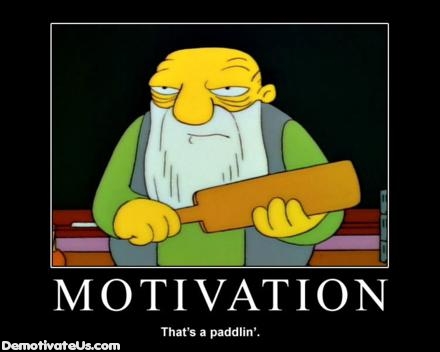

I can see why. Partly it’s the humor value, which is considerable. “What is the simplest, surest, and most direct way of getting someone to do something?” Herzberg’s first answer: the KITA. (Hint: KIT stands for “Kick In The.” Herzberg claims original authorship of this acronym, and given that the article first appeared in 1968 I believe him.) The KITA comes in many forms, including what Herzberg dubs the “negative physical KITA,” i.e. the literal kick. But there are numerous problems with using the negative physical KITA to motivate employees, not least that “it directly stimulates the autonomic system, and this often results in negative feedback.” Translation: the subject may kick back.

Negative autonomic feedback

But Herzberg also makes a substantial contribution to organizational theory, one that’s forced me to do some new thinking on the regular debates we have on the role of incentives in education.

After a brief discussion of the negative physical KITA, Herzberg moves on to what he dubs the “negative psychological KITA,” i.e. making people feel bad unless they do something. The advantages of the negative psychological KITA over the negative physical KITA are considerable, including: “since the number of psychological pains that a person can feel is almost infinite, the direction and site possibilities of the KITA are increased many times”; “the person administering the kick can manage to be above it all and let the system accomplish the dirty work”; and “finally, if the employee does complain, he or she can always be accused of being paranoid; there is no tangible evidence of an actual attack.”

But it is pretty clear to most people that both types of negative KITA do not really produce what we usually call “motivation.” What they produce is movement. The subject moves, but does not become motivated. Hence – and this is the important part – the method is of limited effectiveness. As long as you keep applying KITAs the subject will keep moving, but only as long as you keep kicking and only as far as you kick. To be really effective, you need to do something to get the subject to keep moving – produce ongoing motivation.

Hence most organizations, sensibly enough, turn to positive incentives and discourage managers from using negative ones. And here things get really interesting. Herzberg argues that most of the positive incentives normally used in an attempt to produce motivation are really very similar in their outcomes to negative KITAs – producing movement rather than motivation. The subject subjectively experiences them as positive rather than negative, but objectively the result in terms of work output is similar. You’re just pulling rather than pushing. The subject only moves as long and as far as you pull. Herzberg thus gives these incentives the somewhat paradoxical label “positive KITAs.”

A positive KITA?

Herzberg’s examples of positive KITAs include pay and benefit increases, reduction in work hours, and improved workplace relations (i.e. communications and “sensitivity” training for managers, morale surveys and “worker suggestion” plans).

The positive KITA, Herzberg argues, despite being ubiquitous in the business world, is actually not much more effective than the negative – and it’s a lot more expensive. This is especially true since positive KITAs (unlike negative ones) must be progressive. If you give the worker a $500 bonus this year, when last year you gave him a $1,000 bonus, this objectively positive action will actually be subjectively experienced as negative.

Herzberg argues that a real, self-sustaining motivation can be produced in employees by something he calls “job enrichment.” That sounds like something the warm and fuzzy folks would advocate, but Herzberg actually spends a good deal of time taking the warm and fuzzy folks to task for their inanity. (This provides much of the humor value. It’s also historically interesting – it’s amazing to see how far the warm and fuzzy disease had already spread by 1968.) What Herzberg is arguing for is something more serious than the label implies.

His underlying psycological and organizational theory is a bit too much to recopy it all here, but here’s a capsule summary. He and others did a large number of empirical studies and found that job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction didn’t usually come from the same sources. For example, having a jerk for a boss produces job dissatisfaction, but having a nice boss usually does not produce any job satisfaction. Niceness in bosses simply prevents workers from feeling dissatisfied; it doesn’t actually make the job satisfying.

The key insight to get here is that removing dissatisfaction doesn’t produce any satisfaction, and highly effective motivation comes from producing satisfaction rather than from removing dissatisfaction.

His meta-analysis of the empirical research finds that pay and benefits, job security, company policy, working conditions and on-the-job relationships are all normally associated with levels of dissatisfaction, but rarely with levels of satisfaction. On the other hand, levels of satisfaction are associated with achievement, recognition for achievement, responsibility, advancement, aspects of the work itself, and development of one’s capacities to do the work.

Herzberg’s idea of “job enrichment” is to increase worker’s experiences of the things that provide high levels of satisfaction. Give workers more responsibility and more opportunity to achieve, and then recognize success – most importantly with advancement that brings still more responsibility and opportunity for achievement. The converse of this is that failure must also be “recognized” – primarily through withholding advancement and responsibility rather than through negative KITAs.

I find his theory and evidence persuasive. And it has helped me see a little more clearly the underlying logic behind some objections to education policies like merit pay.

Yet I don’t think this analysis actually does take anything away from the case for merit pay, still less from the case for other education reforms like school choice. If anything, it makes them stronger. And taking account of this analysis will help us make the case more effectively.

Some of the objections to merit pay are based on an essentially Herzbergian conception of worker motivation. Smart people don’t deny that money plays some role in motivating people to do more work. But even among those who don’t advocate touchy-feely romantic delusions about teachers who are angelic beings with no connection to the material world, there is a lot of skepticism that you can get them to work all that much harder just for “a few extra sheckels” (as one of the more sensible critics once put it in a comment here on this blog).

Yet consider what would have to happen for Herzbergian “job enrichment” to occur in the teaching profession. First of all, you’d need an objective measurement of achievement. Then you’d need to give teachers autonomy in the classroom and hold them accountable for results on that metric. And for the accountability to take the form of advancement and increased autonomy (and accountability), you’d need to remove the one-size-fits-all union scale and work rules that dominate the profession.

In other words, it’s not so much the pay that makes merit pay worth trying, as it is the fact that merit pay creates tangible recognition for success. The current system seems almost deliberately crafted to deny teachers as many opportunities for satisfaction as possible. Merit pay is an attempt to create more such opportunities.

It’s worth noting that Michelle Rhee’s proposed two-track system in DC labels the old, union-dominated track the “red” track and the new, merit-based track the “green” track. Rhee understands that what she’s offering isn’t just, or even primarily, more money. She’s offering DC teachers their professional pride.

But school choice looks even better by this light. Test scores would be a limited basis for creating opportunities for Herzbergian satisfaction. On the other hand, if your objective measurement of job performance is parental feedback, the sky’s the limit. In this context it’s worth noting that Herzberg says the only meaningful measure of job performance is ultimately the client or customer’s satisfaction; using any other measure is taking your eye off the ball.

You could even combine the two to create a truly graduated scale of autonomy and accountability. New teachers could be required to use a standard curriculum and be evaluated on how their students – all types of students, not just the rich white ones – progress in basic skills. (That, of course, is the real primary function of test-based accountability – ensuring that kids who face more challenges aren’t just warehoused for twelve years while the rich white kids get an education.) Teachers who prove they can deliver the goods on reading and math for students of all backgrounds could then be given more classroom autonomy and evaluated based on parental feedback rather than test scores. Freedom from test-based accountability is the payoff for proving you can teach basic skills reliably. Schools could set up any number of intermediate arrangements in between “pure” test scores and “pure” parental feedback, with teachers earning more and more recognition and autonomy as they prove more and more their ability to teach effectively.

Looking back at my previous posts on teacher autonomy and satisfaction levels in public v. private schools, the poisonous influence of one-size-fits-all pay scales, and the union-driven destruction of the teaching profession, I can see this is really the framework I’ve been trying to articulate all along. The unions keep bleating about how teachers should be treated like professionals. I agree. They should have autonomy, like professionals – and they should be held accountable for results.

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster