(Guest Post by Jason Bedrick)

At the risk of arousing Greg’s ire, I’d like to talk about the market for education.

In a recent interview, Professor Joshua Goodman of Harvard thoughtfully expressed skepticism that markets could improve quality in education. Whereas I’ve found other attempts to make the “education is different!” argument to be unpersuasive, Goodman makes a few solid points that choice advocates would do well to consider:

I became an economist in part because of Milton Friedman’s argument that vouchers could improve schooling through market forces. At the time, this argument struck me as both revolutionary and obviously right. Competition improves supermarkets, restaurants — why shouldn’t this model apply to schools? It seemed to me that anyone who denied this idea didn’t understand basic economics.

But the more I read, the more I realized that the empirical evidence for choice and market forces improving educational outcomes is thin at best. I found that disappointing and also puzzling, and I have spent some time thinking about why that theory doesn’t match current reality.

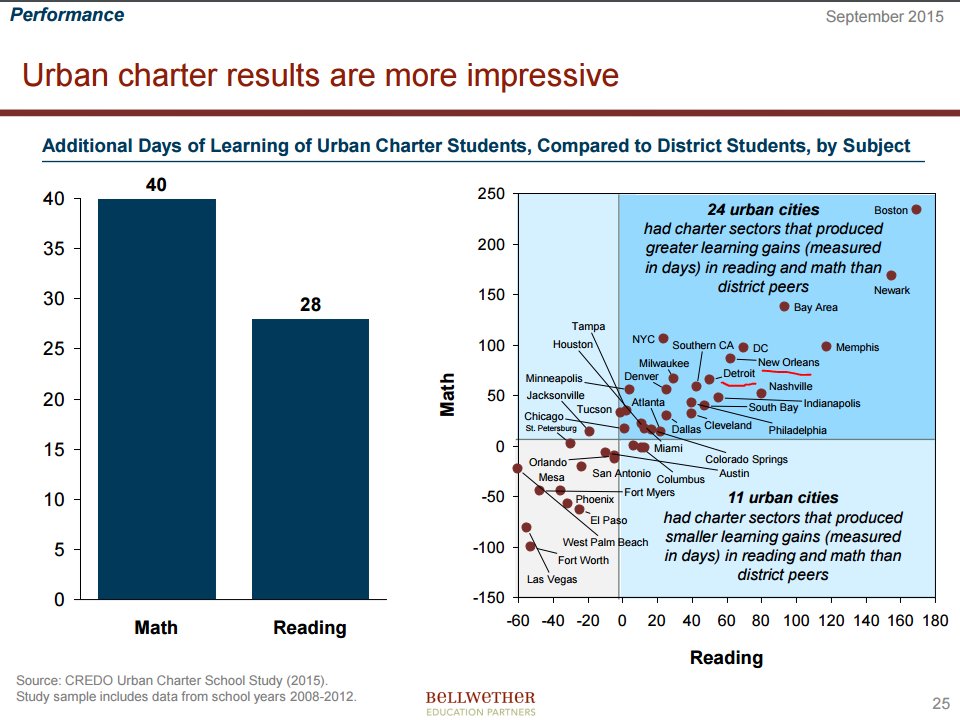

Regarding the evidence, it’s certainly true that none of the catastrophes that school choice critics have predicted have come true. But neither have the policies produced the transformative changes that supporters had promised. Instead, we’ve had a consistent batch of random-assignment studies finding positive but relatively small effects (setting aside the high-regulation disaster in Louisiana). The effects tend to be larger for minorities, parents are much happier, and they cost less per pupil, so I think they’re still worth pursuing even on purely consequentialist grounds, but school choice programs have not been transformative. Why not? Goodman continues:

Here’s what I think the biggest problem in thinking of schools as a classical market. Econ 101 models assume consumers observe product quality. But schools are complicated goods, and quality, particularly a school’s long-run quality, is hard to judge for many parents. It takes a lot of time to figure out whether this school and these teachers are serving my child well. Unlike restaurants or supermarkets, where quality can be judged at the moment of the purchase, school quality reveals itself later. […]

Observing school quality is quite costly, and in many settings there is no credible way to inform future students about the quality of education they are getting. The for-profit college sector is a perfect example of this. Market forces fail to discipline for-profit colleges because for an individual student there’s no repeated game here. Students enroll and only much later realize lousy labor market outcomes. In particular, that students must enroll for a while to see long-run outcomes limits the power of the market to provide discipline. The time it takes to learn that a school is low quality damages the student, and that student’s information may not be transmissible to other students in a systematic or credible way.

Goodman concludes that he does believe “schools could use a bit of market pressure to counteract inertia” because district “monopolies clearly allow many schools to coast on their current trajectories without trying new approaches or investing more effort,” but he is “much more skeptical now than I was before that market forces are some sort of panacea, as they appear to be in some industries.” In the end, he thinks there will “always be a need for public accountability, if only to lower information costs to parents and students.”

I agree with much of this analysis. As I wrote at EdNext today:

There is no panacea. There is no perfect information just as there are no perfect bureaucrats or, for that matter, perfect parents. The question before us is how to design a system with imperfect people and imperfect information that will come as close as possible to providing every child with access to a high-quality education.

Getting parents the information they need to make good decisions is indeed a challenge. As Goodman notes, it is harder to identify a quality education than it is to identify a good meal or a good car. There is a great degree of subjectivity and the payoff is usually far in the future.

The question then becomes what sort of institutions are better equipped to address this challenge. As Lindsey Burke and I argue in a new report published by the Heritage Foundation and the Texas Public Policy Foundation, the technocratic approach of holding schools accountable on metrics that are easily observable and standardized creates perverse incentives that narrow the curriculum, stifle innovation, and can drive away quality schools from participating in the choice program. Instead, what we need are a variety of different third-party reviewers and platforms for parents and students to share their personal experiences in order to provide parents with the information they need.

I won’t rehash the entire argument here. You can either read the report on the short version at EdNext. The main point I wanted to highlight here was that the market is more likely than the government to overcome the information challenge — but for that to happen, there needs to be a large enough market. As I noted:

The K-12 education sector has historically lacked high-quality sources of information about school performance, but to a large extent that is because the vast majority of students attend their assigned district school. With little to no other educational options, there has been little parental need for information to compare competing options. And without much in the way of competition, existing private schools don’t feel great pressure to be forthcoming about performance data. However, as states implement educational choice policies, the demand for information will increase and schools that refuse to share their data will be at a competitive disadvantage. We are already seeing parents to turn organizations like GreatSchools.org and Niche.com to find information about schools they are considering and we should expect to see more organizations emerge as demand increases.

School choice programs that merely fill empty seats are not enough. They won’t bring the transformative change that Milton Friedman and others predicted. Modest choice programs produce modest results. It’s time to go bold.

Posted by Jason Bedrick

Posted by Jason Bedrick