(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Harper’s Magazine wrote a long piece about K-12 education in Arizona.

Sigh

The piece is by-the-numbers approach for Arizona choice opponents, broadly conflating two issues- first how much should we spend in public education? Second should we have parental choice? Blaming choice for all the woes of public education represents a central flaw in the argument, but there is an even bigger problem- the article focuses exclusively on inputs rather than outcomes.

Arizona has an unusual age demographic profile as both a retirement destination and a border state. We have lots of old people (retirees) and lots of young people (large average family sizes for Catholic and LDS families). As a consequence we have a relatively small working age population- and the working age population are the ones paying the bills at any given time. Add to this the practice of urban revenue sharing- where the state gives money to cities off the top- and the fact that Arizona is not a wealthy state, you have the makings of a state ranking near the bottom in spending per pupil compared to other states. Compared to what Arizona spent on public education in say the 1970s, it is much higher now, even per pupil and adjusted for inflation. In other words, it is a tragedy that Arizona did less of this in the minds of some:

Next- public school spending is decided democratically, and is not much impacted by private school choice. Arizona voters have sent a Republican majority to the House continuously since the 1960s. They could have elected a Democrat governor in 2014- they chose not to do so. Voters have their say on overrides- they pass some, they turn others down. Just five years ago they voted on a statewide initiative that would have created a permanent sales tax increase to fund education among other things. It lost overwhelmingly. Proposition 123 referenced in the article included an additional $3.5 billion for schools without a tax increase and barely passed. It is very difficult to make the case, based on the way people vote, that there is a general outcry for higher taxes to fund more school spending.

If Arizona voters chose not to emulate the above chart with the same gusto as the national average, let’s just say it isn’t crazy given how it worked out for everyone else.

The private choice programs meanwhile educate about 4% of the state’s children for about 2% of the funding. When you look across the full gambit of district, charter and private choice programs the districts are the best funded option by a wide margin. The average district school spending per pupil for instance is about four and a half times greater than the average tax credit scholarship. This system is deeply unfair- to districts?

The reason that you see articles like this, the ballot effort, etc. is that the Great Recession was very hard on Arizona’s finances. The state economy is heavily dependent on housing (building houses and golf courses for retirees is a large industry here in the Cactus Patch) and the housing lead downturn hit early and hard here in AZ when people could no longer sell their house in Wisconsin etc. and move to Arizona. State general revenue dropped 20% in a single year. The Obama stimulus and a temporary sales tax increase supported by Governor Brewer staved things off for a time, but eventually there really were per pupil funding cuts. In more recent years the funding has increased, but a lot of grievances can build in a rough decade.

The Harper’s article’s conflating of choice and spending represents a substantial flaw in reporting. If we eliminated the private choice programs tomorrow and most of the kids were forced back to district schools (the high demand charters have wait lists) approximately nothing would change about the fundamentals of public school finance- everyone who is grouchy now would still feel grouchy, and many would find that their problems had increased rather than improved.

An even larger flaw in the Harper article- entirely ignoring outcomes.

During the precise period of economic distress, Arizona lead the nation in academic gains for our students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). NAEP gives 6 tests-4th and 8th grade math, science and reading and we can currently track all six tests from 2009 to 2015 (new results will be available for 2017 in January). Arizona is the only state whose students made significant gains on all six exams. When you net out significant declines from significant increases, the average state improved on just over one test.

While someone else might like to offer some sort of Rube-Goldberg level of complexity argument otherwise, but the above chart makes it seem obvious to me that charter schools are very much helping to drive improvement. Charter schools are approaching 20% of the market and have done much more to put a squeeze on districts than anything in private choice.

So essentially what we have here is a situation in which there has been belt-tightening, where academic results are improving faster than anywhere else, and where the incumbent providers (districts) are feeling very put upon . There are much larger factors at work than private choice, and overall the systemic bet that Arizona lawmakers put on choice has paid off handsomely outcome-wise.

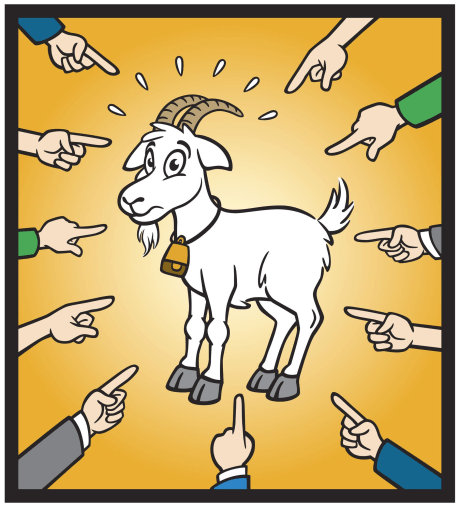

Arizona has a long way to go and a short time to get there, but it is hard to realistically ask for more than “leading the nation in gains.” You can of course prefer to spend more money (this is why we have elections) but choice opponents have essentially made private choice programs into a scapegoat for other frustrations.

Posted by matthewladner

Posted by matthewladner