Today AEI released a systematic review by Collin Hitt, Mike McShane, and Pat Wolf on the relationship between changes in test scores and changes in later educational attainment in rigorous studies of school choice programs. I’ve been writing and talking about this for some time now, inspired to a large degree by informal conversations with the authors of this new report. Now they have made the point more systematically.

They examined every study of school choice programs with both test score and attainment effects, consisting of “39 unique impact estimates across studies of more than 20 programs.” They examine whether the direction and significance of the estimated effects of those programs on test scores are consistent with the direction and significance on attainment. They are not.

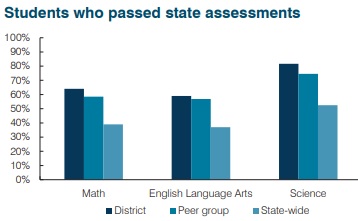

They find: “Across the studies we examine, there is no significant or meaningful association between school choice impacts on math scores and high school graduation or college attendance. Nor are ELA impacts meaningfully associated with high school graduation rates. Under some tests, the relationship between ELA impacts and college attendance are significant—but the relationship is weak in magnitude, and the sample of studies is far narrower for college attainment than for high school graduation.”

Keep in mind that the policy relevant question is not whether individual changes in test scores are correlated with individual changes in attainment. There is some research that has found this relationship (see for example Chetty, et al), but a surprising number of studies find no or only a weak relationship between individual gains on these near-term and later-term measures of success. But none of them directly address the policy relevant question of whether aggregate test score changes at the school or program level are predictive of aggregate changes in attainment.

If we are going to judge schools or programs as good or bad based on changes in test scores, then those aggregate measures (not individual results) should be predictive of later success. The fact that they are not, at least when judging school choice programs and schools, suggests that there is something fundamentally wrong with how we have approached public regulation (wrongly called “accountability”) of those programs. You can’t regulate the quality of schools and programs if you can’t predict their quality.

Posted by Jay P. Greene

Posted by Jay P. Greene