(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Reviewing Arizona’s ESSA plan the Fordham event the other day inspired a growing sense of dread as I trudged through page after page of extreme complexity regarding the state’s plan to grade schools A-F. “If Jurassic Park scientists spliced the DNA of a Franz Kafka nightmare with a Rube Goldberg machine, it would look something like this…” I recall thinking to myself six or so pages in (less than halfway) through the description of the formula.

When we discussed the concept with Arizona lawmakers originally, the idea was a straightforward mix of 50% proficiency rates, 25% gains for all students, and 25% gains for the students who scored at the bottom 25% on the previous year’s test. This formulation is both easily understood and provides an incentive for schools to avoid having students falling hopelessly behind. Why settle for something tried, true and elegant when you can develop your own new and improved version?

An ultra-complex formula provides opportunity for things to go wrong. Grades were released today, they are almost entirely based on AZMerit scores, and the grades failed the very first check of face validity I tried from schools in my own neighborhood. The above charts show AZ Merit scores from Ingleside Middle School (Scottsdale Unified) and Archway Veritas. Respectively these are the closest and the second closest schools to where I live.

Greatschools gives Archway Veritas a 10 out of 10 ranking and Ingleside an 8 out of 10. Hard to quibble with that- Ingleside’s scores are above state averages while Veritas scores are far above state averages.

Under the newly released Arizona grades, Ingleside received a “B” from the state, while Archway Veritas received a “C.” Despite the fact that Archway students had a 30% proficiency advantage in math, and a 24% proficiency advantage in ELA, they received a lower grade. Hmmm. This alas is simply the first test of face validity I ran, which lasted all of two minutes. If I were to spend a bit more time, I’m confident I could find even more inexplicable results.

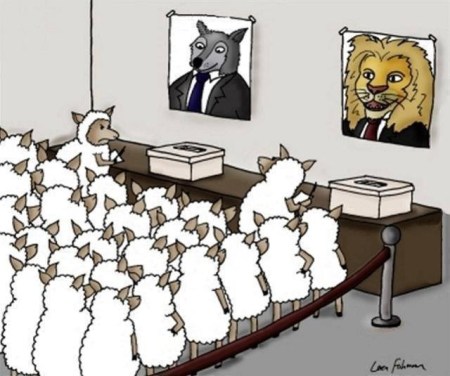

Arizona suspended letter grades years ago due to the introduction of new tests. I know many of the people involved in the effort to revise the formula to be outstanding people who care deeply about improving Arizona K-12. Nevertheless, these grades lack face validity in my book and ought to be revised using a straightforward formula. Failing that, the legislature should adopt new school labels along the lines of “Blue” “Green” and “Poka Dot” to satisfy the feds and leave the task of ranking schools to private platforms such as Greatschools and others, which is where the eyeball traffic resides already. The state, alas, seems unequal to this task.

Anyone from either districts or charter schools will find plenty of things to complain about with a bit of examination. They will be upset. They will have a right to be upset. Fortunately Arizona’s nation leading academic progress is being driven from the bottom up.

Posted by matthewladner

Posted by matthewladner