(Guest post by Greg Forster)

On Monday the Boston Foundation released a study by researchers from Harvard, MIT and Duke, examining Boston’s charter schools and “pilot” schools using a random assignment method (HT Joanne Jacobs).

Pilot schools were created in Massachusetts in 1995 as a union-sponsored alternative to charter schools, which came to the state a year earlier. Pilot schools are owned and operated by the school district. Like charter schools, pilot schools serve students who choose to be there (though it’s easier to get into a charter school than a pilot school; see below). Like charter schools, pilot schools have some autonomy over budget, staffing, governance, curriculum, assessment, and calendar. Like charter schools, pilot schools are regularly reviewed and can be shut down for poor performance.

There are two main differences between charter schools and pilot schools. First, the teachers’ unions. Pilot schools have them, and all the shackles on effective school management that come with them. Charter schools don’t.

Second, some pilot schools are only nominally schools of choice, not real schools of choice like charter schools. Elementary and middle pilot schools – which make up a slender majority of the total – participate in the city’s so-called “choice” program for public schools, and thus have an attendance zone where students are guaranteed admission, and admit by lottery for the spaces left over. So while on paper everyone who goes to a pilot school “chooses” to be there, some of them will be there only because the city’s so-called “choice” system has frozen them out of other schools. The students compared in the study are all lottery applicants and are thus genuinely “choice students” – they are really there by choice, not because they had no practical alternatives elsewhere. However, the elementary and middle pilot schools are not “choice schools.” (Pilot high schools do not have guaranteed attendance zones and are thus real schools of choice.)

The Boston Foundation examined two treatment groups: students who were admitted by lottery to charter schools and students who were admitted by lottery to pilot schools. The control groups are made up of students who applied to the same schools in the same lotteries, but did not recieve admission and returned to traditional public schools.

As readers of Jay P. Greene’s Blog probably know already, random assignment is the gold standard for empirical research because it ensures that the treatment and control groups are very similar. The impact of the treatment (in this case, charter and pilot schools) is isolated from unobserved variables like family background.

The results? Charter schools produce bigger academic gains than regular public schools, pilot schools don’t.

The two perennial fatal flaws of “public school choice” would both seem to be at work here. First, public school choice is always a choice among schools that all partake of the same systemic deficiencies (read: unions). Choice is not choice if it doesn’t include a real variety of options. And second, public school choice typically offers a theoretical choice but makes it impossible to exercise that choice in practice. In this particular case, if each school has a guaranteed-admission attendance zone, the practical result will be fewer open slots in each school available for choice. (Other kinds of public school choice have other ways of blocking parents from effectively using choice, such as giving districts a veto over transfers.)

Charter schools are only an imperfect improvement on “public school choice” in both of these respects. Charters have more autonomy and thus can offer more variety of choice, but not nearly as much as real freedom of choice would provide. And with charters, as with public school choice, government controls and limits the admissions process.

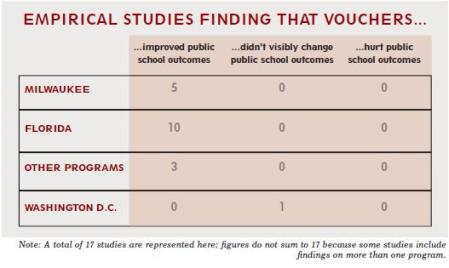

But charters are an improvement over the status quo, even if only a modest one, as a large body of research has consistently shown.

There are some limitations to the Boston Foundation study, as with all studies. Pilot high schools are not required to admit by lottery if they are oversubscribed, while charter schools are. (Funny how the union-sponsored alternative gets this special treatment – random admission is apparently demanded by the conscience of the community when independent operators are involved, but not for the unions.) Of the city’s pilot high schools, two admit by lottery, five do not, and one admits by lottery for some students but not others. Thus, the lottery comparison doesn’t include five of the pilot high schools. It does include three high schools and all of the elementary and middle schools.

As always, we shouldn’t allow the limitations to negate the evidence we do have. Insofar as we have evidence to address the question, more freedom consistently produces better results, and more unionization consistently doesn’t.

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster