(Guest post by Greg Forster)

On Saturday the Cincinnati Enquirer ran a story on how Ohio is sitting on a bunch of student outcome data for the EdChoice voucher program and neither doing anything with them nor releasing them to researchers who could do something with them. I’m told it was picked up by AP.

The story is generally good. Transparency is always preferable. Student privacy concerns do limit the extent to which the state can release data to the general public, but the state ought to be able to release a lot more than it has, and it also ought to license private researchers to use more sensitive data on a restricted basis, just as NCES does.

The story’s author, naturally enough, wanted to provide what little data are available. So she provided the number of EdChoice students who failed the state test in each subject.

Readers of JPGB probably already know this, but any outcome measurement that just takes a snapshot of a student’s achievement level at a given moment in time, rather than tracking the change in a student’s achievement level over time, is not a good way to measure the effectiveness of an education policy. A student’s achievement level at any given moment in time is heavily affected by demographics, family, etc. Growth over time removes much of the influence of these extraneous factors (though obviously it doesn’t remove absolutely all the influence, and further research controls or statistical techniques to remove these influences more are preferable).

Moreover, EdChoice program is specifically targetd to students in the very worst of the worst public schools. These are students who are starting from a very low baseline. We should expect these students’ results to remain well below those of the general student population even if vouchers are having a fantastically positive effect. So the need to track students over time rather than simply take a snapshot of their achievement levels is especially acute here. Only a rigorous scientific study can examine whether the EdChoice voucher program is improving these students’ performance – and to do that we’d need the data that the state is sitting on.

Also, a binary measurement of outcomes (pass/fail) is never as good as a scale. The state is sitting on scale measurements of the students’ performance, but from the Enquirer story it appears that it won’t release them.

And the Enquirer was only able to obtain these pass/fail results for 2,911 students out of about 10,000 served by the program.

All that said, I don’t blame the Enquirer for reporting what few data were available. The story is focused on the state’s stinginess with data, not the performance of the program as such.

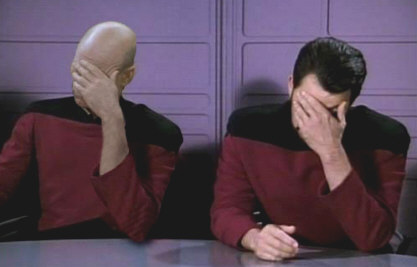

But what headline did the paper put on the story?

“Ed Choice Students Failing.”

Of course the story’s author doesn’t choose the headline. And the person who did choose the headline almost certainly had to do so under intense deadline pressure, without much space to work with, and with no knowledge about the issues other than what could be gleaned from a very quick and superficial reading of the story. Still, since the story clearly focuses on the issue of the state’s sitting on valuable data without using them, you would think they could come up with something like “Voucher Data Not Used.”

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster