(Guest post by Greg Forster)

My Win-Win findings read out loud on The View (check it out at the 9:30 mark).

I promise to remember y’all now that I’ve come into my kingdom.

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

The Economist provides a current state of play for the MOOC space, Georgia Tech announces a new ultra-low cost Masters Degree in analytics, and EdX has a summary of who uses their courses, earns credentials etc.

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

So in a delightful episode of the television series classic Buffy the Vampire Slayer the Scooby Gang discovers that the demon terror du jour is approximately six inches tall. The demon babbles on about his fearsome power as the Dark Lord of Nightmares, only to have classy Giles admonish the good guys for taunting the boastful mini-monster in preference to a quick dispatching and well deserved stomp.

So…for some reason this scene came to mind when I read a letter that the Massachusetts Charter School Association sent to Elizabeth Warren opposing the nomination of Betsy DeVos for Secretary of Education.

Ok calm down-I know you have a lot of questions: Yes the same charter school association that helped burn through tens of millions of other people’s money only to lose decisively on a ballot measure to allow 12 new charters a year to open in the state. The same association whose sector is too small to meet the minimum reporting requirements in either Massachusetts or even Boston. Yes the same Elizabeth Warren that turned on them when they went to the ballot.

Well then, what do the wee-tiny Dark Lords of the Bay State’s safely contained charter sector have to say for themselves?

By all independent accounts, Massachusetts has the best charter school system in the country. We are providing high quality public school choices for parents across our state. Our urban schools are serving the highest need children in Massachusetts, and are producing results that have researchers double-checking their math. These gains held across all demographic groups, including African American, Latino, and children living in poverty.

(https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/03/18/gains-boston-charter-school… according-six-year-study/hCpVGMeEQvNODUvB6bXhcK/story.html)

The cornerstone of the Massachusetts charter public school system is accountability. The process of obtaining and keeping a charter is deliberately difficult. The state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education is the sole authorizer and historically has approved only one out of every five applications. Once approved, each charter school must submit to annual financial audits by independent auditors and annual performance reviews by the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Every five years, each charter must be renewed after a process as rigorous as the initial application process. For-profit charter schools are prohibited by Massachusetts law.

Tremble before their fearsome technocratic awesomeness or they will DESTROY YOU!

Okay, so here is a new independent evaluation for you- MA charters are apparently effective for many of the small number of kids who will ever have the chance to attend them. That’s wonderful, but outside of that one can’t help but notice that very few people in MA, including Senator Warren, seemed overly impressed with either their bureaucratic compliance or test scores during the initiative. I can’t say I’m overly impressed with a sector that has approximately zero prospects for growth.

Moreover, if you find yourself stalemated at the legislature and crushed at the ballot box, does the scroll inside the “Break Glass in Case of Emergency” box say “Write a pompous letter to someone who was already a ‘no’ denouncing someone who supports your cause?” Let’s ask the 8-Ball whether it would be good to follow that advice:

Oh and by the way, the independent evaluations referenced in the letter that like Boston charters also like Detroit. As Max Eden noted:

The 2013 study of Michigan charter schools by Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) found that “charter students in Detroit gain over three months per year more than their counterparts at traditional public schools.” A 2015 CREDO study of 41 major cities concluded that Boston, Newark, Washington, D.C., and Detroit, “provide essential examples of school-level and system-level commitments to quality that can serve as models to other communities.

Some of these charter sectors-like Detroit btw- delightfully have the opportunity to grow and serve more students. Others apparently prefer to accept their containment and babble about their fearsome powers. Somehow it is not hard to imagine why Massachusetts voters administered a ballot box stomp.

(Guest Post By Jonathan Butcher)

Are American classrooms improving? After a century of government and non-government interventions, we hope so. But we’ll need to look someplace other than Ed Boland’s The Battle for Room 314. A visitor to earth who had never seen a school before might be unable to distinguish between demilitarized zones and Boland’s class. Drugs, guns, obscene speech and behavior—imagine if Quentin Tarantino rewrote the script for Dangerous Minds.

We learn near the end of Room 314 that Boland’s school, Union Street, ranked in the bottom five percent of New York’s schools, so his class is not representative of the U.S. We hope things would have improved since other hard-luck education stories like Up the Down Staircase and the Morgan Freeman film Lean on Me, these works now some 60 and 30 years old, respectively. Room 314 forces us to look for good news elsewhere, because it’s not found at Union Street.

Room 314 is a memoir, not a policy guide, even though Boland offers recommendations in the book’s conclusion. The author is a 40-something New Yorker who leaves his successful career in fundraising to teach in a New York City public school. He gives an account of his year spent trying to make sense of American teenagers with absent or unstable parents. Boland leaves little to the imagination and tells the story with the same salty language that his students use in class. Be warned, it’s brutal and explicit storytelling at times.

Because this is a book about public schools, Boland’s personal story cannot help but expose familiar policy problems. Halfway through the school year, Boland and his fellow ninth grade teachers plan to reconfigure the classrooms to break up the most disruptive students. The teachers agree to teach an extra period.

Enter the union. The representative says, “If management sees that teachers are willing to work more without more compensation, they’ll hold that against us during the next round of negotiations… We have to adhere to the contract strictly or the whole thing falls apart.” Boland says his class has already fallen apart.

The demoralizing union tactics are not lost on him. In his suggestions for system-wide improvement, he says:

“In simplest terms, unions must be more willing to work with the administration so they can fire the least effective teachers; change lockstep compensation; reconsider evaluation, seniority, and tenure; and create incentives to put the best teachers in the neediest schools.”

Still, he understands his students’ obstacles are more than he can overcome in class. He says that one of his students wants to attend Columbia University after participating in a model United Nations competition on campus: “I didn’t like knowing that Solomon’s fate was already pretty-well sealed by his ethnic surname, his lousy zip code, and his mother’s measly income.”

The conflicting ideas in Room 314 are whether Boland was unprepared or his students had too many challenges at home or the school somehow failed them all. An NPR review of Room 314 written by a teacher says, “Had Boland stuck around another year or two…he might have written his story quite differently.” Boland says Union Street was under new leadership shortly after he left, and it was unclear how many students were to repeat a grade—so there are no guarantees. The NPR reviewer is critical of Boland’s lesson planning and inability to connect with his students. Fordham’s Robert Pondiscio (who worked for Boland at a non-profit) is less critical of Boland and blames inadequate teacher preparation programs for those headed to inner-city schools.

Regardless, Boland deserves credit for taking a year and all the compassion he could muster to protect, console, and, at times, even teach a frightening group of teenagers. His criticism of the union is noted, but his other calls to action like different integration laws and more funding fall flat. There is not enough taxpayer money in all of Albany (or Washington) to solve Room 314’s problems.

(Guest post by Greg Forster)

OCPA’s Perspective carries my latest under the somewhat discouraging title “Ed Choice Mythbusting Never Ends.” At least I’ll never be out of a job:

The funniest thing in the article is where McCloud mocks the emergence of Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) and then complains about precisely the problem ESAs solve. After making fun of the choice movement for switching from vouchers to ESAs—because apparently it’s a bad sign if you’re willing to move from a good idea to a better one—McCloud asserts that “vouchers would inflate the cost of private education.”

Indeed, vouchers do inadvertently raise private school tuition. That is one reason the movement is switching from vouchers to ESAs, which allow parents to buy education services without creating an artificial tuition floor for schools. It’s also true that even ESAs raise economic demand for education services in general—but that’s just another way of saying they empower parents to pay for those services!

McCloud’s article provides a public service in one respect: It collects almost all the school choice myths in one place. Maybe I don’t mind so much if the defenders of the status quo make my job easy after all.

As always, your thoughts are appreciated!

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Arizona Republic columnist Bob Robb wrote a piece on Arizona Governor Doug Ducey’s recent State of the State address. Money quote:

Ducey wasn’t a party to the deep cuts to K-12 education that were made after the bursting of the housing bubble knocked a big hole in state revenues. In fact, during his governorship, per-pupil spending, adjusted for inflation, has gone up, not down. Try to find an acknowledgement of that in the education funding debate.

In his speech, Ducey pointed out that “Arizona students are improving faster in math and reading than any other kids in the country.” That’s true.

Yet, there is a curious lack of curiosity about this development. In fact, Matt Ladner, a scholar with the Foundation for Excellence in Education, is about the only person in the state documenting it and inquiring about its causes. Everyone else is crying in their beer.

Bob’s kind remarks require two clarifications. First I made a professional transition a couple of months ago. Second, it is only bloody well near everyone else crying in their beer in Arizona, rather than actually everyone else. Crying in your beer is a bad look after all. A select few of us are just way too busy celeNAEPing our progress and trying to figure out ways to get more for it.

(Guest post by Robert Costrell)

Background: The essay below was written by invitation for Education Week, to be published along with other commentaries, in conjunction with the release of Rick Hess’ annual “edu-scholar” rankings this month. The invitation was to respond to the prompt below. Ed Week accepted the essay for publication, but then pulled it when I declined to submit to their extensive requested revisions.

Ed Week’s Prompt: “It’s no great secret that the American professoriate tilts to the left, particularly in the social sciences and humanities. The disjuncture between the academic mainstream and a large swath of the American public has been especially evident during this year’s heated presidential campaign and in the course of the Trump transition. What should public-minded academics make of this? Is it a problem if academic sentiment generally aligns with one side of the political spectrum? Does it create challenges for the academy or limit the ability of academics to offer policy ideas or engage in a more robust public debate? What, if anything, should publicly-engaged academics try to do about any of this?”

My Essay:

Education Policy Scholarship a Bright Spot in a Depressing Political and Academic Era

In a depressing era for politics, policy, and academia, our little field of education policy scholarship stands as a bright spot – for now, at least. The current presidential transition actually illustrates the point. Unlike other nominations, the debate over Betsy DeVos has been well informed by policy scholars, regarding Michigan’s charter schools, a central element of Ms. DeVos’ record. Our colleagues have debated what the evidence says or does not say and how the policy choices in Michigan may or may not have worked. Yes, some political posturing has crept into that debate, even among our public scholars, but compared to what we have seen during and beyond the long presidential campaign, and over many decades in academia, our field’s contribution to this current episode is not bad.

It was not always thus. Thirty years ago, education policy scholarship was a backwater. With some notable exceptions, it was non-disciplinary, as opposed to inter-disciplinary. Since then, high-caliber economists, political scientists, legal scholars, and others have brought their disciplines into a weak field and, on the whole, have strengthened it. Consider the transformation of our main professional organization, the Association for Education Finance and Policy (AEFP). AEFP founded an impressive new journal (Education Finance and Policy, MIT Press) and our annual conferences feature growing numbers of well-trained, bright young scholars, interacting with policy practitioners. Yes, political predispositions often lurk beneath the surface, and sometimes erupt, but in general they are well-contained. By contrast, just look at those fields – including some major ones – where annual conferences are hijacked by destructive elements seeking to academically boycott their colleagues from Israel. That kind of thing does not happen at AEFP.

Looking more broadly to the question posed above, regarding the current impact of academia’s leftward tilt, there are definitely reasons for concern. Ideally, personal political convictions of the faculty should not matter, if we all adhered to the historical norm for the academic temperament, checking our political, religious, and other personal passions at the university door. But over the nearly four decades since I entered the professoriate, that norm has been increasingly abandoned. Far too many of our colleagues want our academic freedom, but not the “corresponding duties” of scholarly restraint emphasized by the AAUP a century ago. Moreover, many universities now face student activists born and bred in this environment, who exacerbate matters by demanding ever-more politicized compliance on our part with specified stances and speech, abetted in too many cases by pusillanimous administrators.

A politically lop-sided professoriate will obviously have reduced influence on public policy when its side is out of power. Yes, there is a role for the loyal scholarly opposition. Indeed, historically Democratic and Republican scholars would simply switch places, between government and academia, when elections so determined. But, what now? Where are Republican state governments to turn for academic policy expertise after their dramatic ascendancy across the country since 2009? Moreover, when a State House switches power again, where will the few Republican academics who served those administrations find an academic home, from which to provide their loyal scholarly opposition?

This is not only a matter of the service we can provide our governments, but conversely, the immense benefit we can derive as scholars from a stint of public service. I speak from personal experience of the insights – and humility – acquired during seven years of serving three Republican governors in Massachusetts facing veto-proof Democratic legislatures. Ironically, I found far more political tolerance and dialogue in that divided State House than in the academic environment from which I had come at the University of Massachusetts.

The recent presidential vote – populist in result – suggests the problems in academia may run deeper than a simple lack of balance between right and left. I agree with New York Times columnist David Brooks and the Brookings Institutions’ William Galston, writing in the Wall Street Journal, that our national problem has been the collapse of the broad center. If we are to have political identifications in academia (not my first-best solution), we should try to restore the presence of and dialogue between the center-right and center-left.

As for education policy scholarship, to stay relevant, we should learn from the disastrous examples in so many other parts of academia. We should resist the encroachment of identity politics, which has proven so corrosive, both to academia and the comity of our body politic. We should also resist the hubris to which policy scholars can succumb. When a publicly-engaged scholar like MIT economist Jonathan Gruber is repeatedly caught on video bragging that he put one over on the “stupid” American public in his design features for Obamacare, should we be surprised when large swaths of that public vote against the whole idea of policy expertise?

Let us borrow Benjamin Franklin’s famous warning after the Constitutional Convention, much quoted in the aftermath of our recent election. We in education policy scholarship have a good field, “if we can keep it.”

——————————————————————

Robert Costrell is professor of education reform and economics at the University of Arkansas. He served MA Governors Paul Cellucci, Jane Swift, and Mitt Romney, 1999-2006, as policy research director, chief economist, and education advisor.

(Guest Post by Jason Bedrick)

Once again, the editors at the New York Times have allowed their bias against school choice to get in the way of reporting facts.

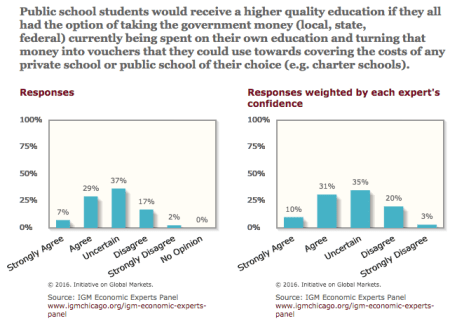

On Friday, the NYT ran a blog by Professor Susan Dynarski with the incredibly misleading headline (which, in fairness, she likely didn’t write): “Free Market for Education? Economists Generally Don’t Buy It.”

Based on that description, you might think that a survey of economists found that most economists think a market in education wouldn’t work, or at least that there were more economists who thought it wouldn’t work than thought it would. Well, not quite. Dynarski writes:

But economists are far less optimistic about what an unfettered market can achieve in education. Only a third of economists on the Chicago panel agreed that students would be better off if they all had access to vouchers to use at any private (or public) school of their choice.

Follow the link to the 2011 IGM survey and you’ll find that 36% of surveyed economists agreed that school choice programs would be beneficial–but only 19% disagreed and 37% expressed uncertainty.

Scott Alexander of the Slate Star Codex blog writes:

A more accurate way to summarize this graph is “About twice as many economists believe a voucher system would improve education as believe that it wouldn’t.”

By leaving it at “only a third of economists support vouchers”, the article implies that there is an economic consensus against the policy. Heck, it more than implies it – its title is “Free Market For Education: Economists Generally Don’t Buy It”. But its own source suggests that, of economists who have an opinion, a large majority are pro-voucher. […]

I think this is really poor journalistic practice and implies the opinion of the nation’s economists to be the opposite of what it really is. I hope the Times prints a correction.

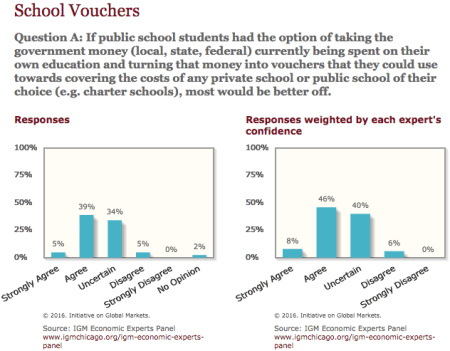

Actually, it’s even worse than that. Oddly, Dynarski did not include the results from the more recent 2012 IGM survey, in which the level of support for school choice was higher (44%) and opposition was lower (5%), a nearly 9:1 ratio of support to opposition. When weighted for confidence, 54% thought school choice was beneficial only 6% disagreed.

We should give Professor Dynarski the benefit of the doubt and assume that she didn’t know about the more recent results (though they pop right up on Google and the IGM search feature), but the NYT deserves no such benefit for its continuing pattern of misleading readers about the evidence for school choice.