Image courtesy of Murin / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

(Guest Post by Patrick Wolf)

Subsidiarity is the principle that decision-making authority should be delegated to the lowest reasonable level. Why? Because people in localized areas like states, communities, schools, and families have contextual knowledge that helps inform their decisions – knowledge that centralized administrators in far-away places (like, say, Washington, DC) lack. Subsidiarity also is justified because small communities more directly reap the benefits when things go well for their members and suffer the consequences when things go poorly, meaning community decision-makers have strong incentives to get things right.

That brings us to the new Federal Lunch Program nutritional mandates, spearheaded by First Lady Michelle Obama and issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in January of 2012, to great fanfare. You might consider them to be “The Common Core” of school nutrition policy, embodying the thinking of the best minds in Washington regarding what every child in America should consume for lunch. As Kyle Olson at EAG News reports, implementation of the nutritional reforms hasn’t quite been as easy as pie.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released the official testimony of Kay Brown, the Director of Education, Workforce, and Income Security for the organization, regarding GAO’s investigation of the experience on the ground regarding the nutritional mandates. To be sure, schools retained the ability to develop their own lunch menus, but they had to fit them into the strict guidelines for caloric intake and food types issued by the feds. Not surprisingly, there have been problems. For example,

The meat and grain restrictions…led to smaller lunch entrees, making it difficult for some schools to meet minimum calorie requirements for lunches without adding items, such as gelatin, that generally do not improve the nutritional quality of lunches. (p. 1)

So, to meet the nutritional regulations imposed by Washington bureaucrats, some schools had to make their lunches less nutritional. Nice.

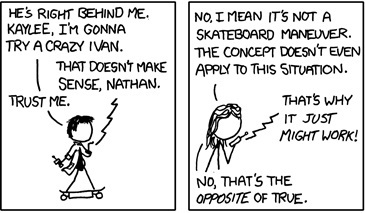

The GAO testimony also mentions that some schools had to eliminate the cheeseburgers, beloved by high school students, because the feds redefined cheese as meat, leaving cheeseburger meals too meat-dominant for Washington’s liking. (“You are a meat! No, I am a dairy product! No, you are a meat because I say you are a meat!”) To save the cheeseburger, one school even shrunk the actual meat portion to a puny 1.5 ounces so that it could be blanketed by a slice of cheese (which is a meat by the way). One can envision hundreds of teenagers, as opposed to one little old lady, shouting “Where’s the beef?!”

Students, predictably, dislike the changes and have taken steps to undermine them, most notably by throwing away much of the highly nutritional food that now must be provided to them. Teachers report that students are less attentive during the final class period, when they have run out of energy due to inadequate caloric consumption during the day. Coaches report student athletes who can’t perform during practice because they are famished. Some schools have quit the Federal Lunch Program, denying their low-income students government lunch subsidies, just to escape the federal requirements. Let’s just say this isn’t going so well.

When I was in high school, I was a 5-foot-6-inch, 120 pound speech-and-debate guy. Sometimes I would eat lunch with Steve Janey, a 6-foot-8-inch, 200 pound center on our basketball team. Steve had trouble keeping weight on his large frame. The nice lunch ladies would sometimes slip him an extra hamburger patty, and I would give him food off my plate that I didn’t need or care to eat. It took some work to keep Steve full and fit, but we all pitched in because it benefited us if he was the beast in the low post that we wanted him to be. Subsidiarity.

The new school lunch nutritional standards were not designed for the Steve Janey’s of this world. They were designed for the “typical American student” who really doesn’t exist. Young people come in all shapes, sizes, and nutritional needs. Athletes and children on farms burn thousands of calories per day more than do brainiacs. How could we possibly expect that a single set of nutritional standards would be a good fit for all school children, in the distinctive communities that dot our country, and that they would passively eat their peas and carrots and like it?

Adhering to subsidiarity does not mean always delegating to the max. For example, the President and the Congress should decide which national security secrets should be released to the public, not some low-level government contractor. National security affects the entire nation equally, and federal government officials bear the consequences as much as just about anyone except members of our armed forces when security is degraded. But school lunches aren’t national security. Let communities decide what is a fitting lunch for their students, and the high school students themselves choose from higher-calorie or lower-calorie meals based on their particular needs. If not, Washington is likely to get a good old fashioned food fight.

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Posted by matthewladner

Posted by matthewladner