(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Steven Brill brings the pain in a fantastic new article on NYC rubber rooms. Money quote:

“Randi Weingarten would protect a dead body in the classroom. That is her job.”

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Steven Brill brings the pain in a fantastic new article on NYC rubber rooms. Money quote:

(Guest post by Greg Forster)

Quick, before it leaves theaters, go see Ponyo, the latest film from Japanese visionary Hayao Miyazaki. As I’ve written before, Miyazaki’s movies fall into two categories: family features and challenging epics. Ponyo is definitely on the family side of the equation. But I went without kids and loved it as a grown-up, so don’t be deterred. There’s plenty here to enjoy.

Well, OK, maybe not everyone should rush out to see it. If you’re the kind of person who would go to to a movie about the fantastic adventures of a five-year-old whose chance encounter with a magical fish-girl threatens to upset the balance of the magic and human worlds, possibly destroying both, and spend the whole time saying to yourself things like, “Hey, no five-year-old could push something that size on his own! And how come he has the vocabulary of a twelve-year-old?” maybe Ponyo is not for you.

But everyone else should go.

If you plan to see it, stop here. I’m not going to spoil the ending, but the movie reveals itself slowly (as many Miyazaki movies do) and you’ll probably enjoy it more if you don’t know much about it going in.

If, however, you need to be convinced, read on.

Ponyo is the daughter of a sea-wizard and lives with him at the bottom of the ocean. Her father hates the human world and forbids her to see it, which naturally makes her eager to go. But she gets into trouble (of course) and is rescued by a five-year-old boy named Sosuke, who protects her and takes care of her until her father comes to take her back to the sea.

Ponyo, starved for love in the house of her hard-hearted father and awed by the self-giving kindness of Sosuke, decides she’d rather be human. She gets into her father’s magical works and manages to open a rift in the barrier between the magical and human ecosystems, allowing her to change herself to assume a human form – but also causing a catastrophic disruption of the human ecosystem that leaves an entire town underwater and threatens to do worse.

After her transformation, Ponyo has a foot in both worlds – though she appears human, she can still work magic. Much of the movie’s charm comes from the shared delight of mutual discovery between Ponyo and Sosuke. Sosuke marvels as Ponyo turns a toy boat into a real boat and fixes broken household appliances with a glance; Ponyo is equally blown away by the delights of flashlights, ham sandwiches, and warm towels straight out of the dryer.

But back in the sea, her sea-wizard father and her mother (whose identity I’ll keep under wraps) determine that the only way to close the rift she’s opened and save the human world from destruction is for Ponyo to become entirely one thing or the other. She must either return to the sea, or else complete the transformation, giving up her magic and becoming fully human.

Of course they know Ponyo will be miserable if she returns to the sea, but to become fully human she must be drawn across the divide by a human love – by Sosuke. However, in the process of drawing Ponyo over that love will be tested. Does Sosuke really take care of Ponyo because he cares about her well-being? Or is he just interested in her because she’s magical and fascinating? If Sosuke fails the test, Ponyo’s desire to become human will destroy her.

Ponyo’s mother has faith in the genuineness of human love and thinks it’s better for Ponyo to risk death than to abandon her desires, so she arranges for the transfer. But her father hates humans and fears Sosuke’s love will fail the test. He may or may not be laying plans to interfere.

But all this plot is really irrelevant to the joy of the film. What Miyazaki is giving us here – besides gorgeous visuals and a delightful story in its own right – is a vision of how the world of humanity relates to the world of nature. “Magic” in this movie is symbolic of the spiritual significance most of us attribute (on some level) to nature.

Don’t get me wrong! The bad, human-hating kind of environmentalism is condemned pretty clearly. (This is a big step for Miyazaki, who has not been so enlightened about this in the past.) Ponyo’s sea-wizard father not only hates humans, but actually dreams of one day wiping them out – because he hates their impact on the environment. Those who see the ecosystem as something with its own inherent integrity apart from humanity, such that any impact of humanity’s existence on the natural world is bad simply as such, are implicitly wishing for humanity’s annihiliation.

In fact, we learn at one point that the sea-wizard father was born human and has somehow himself crossed the very same border Ponyo wants to cross, only in the other direction. The desire of some humans to get into nature – which drives so much of what now passes for environmentalism – is really a desire to get out of humanity. As the wizard says, they need to abandon humanity to serve the earth.

What do you know about humans? They treat your home the same way they treat their fithly black souls! I was human myself once. I had to leave all that behind to serve the earth.

But what if the shoe were on the other foot? What if we could “become one with nature” not by dragging humanity down, but by pulling nature up?

That’s the thought I couldn’t stop having as I watched the extended scene in which the rift opens between the human and magical worlds. The way Miyazaki does it, it’s breathtaking. Everyday things in our everyday world suddenly become magical. Not magical like wands and rings and such D&D fantasies – magic as a tool for humans to use – but magical with its own life and its own distinct nature. The road Ponyo’s mother drives down to get to work every day, with the forest on one side and the sea on the other, suddenly becomes bursting with little gods and goddesses all around them.

That’s what Ponyo’s desire to become human represents – against her father’s cold, self-loathing desire to have nature instead of humanity, her desire for love drives nature to come up alongside humanity, with its own personality, wanting to love us the way we love it. And on those terms we really can become one with nature.

Tree-huggers have got the wrong idea, because there’s nothing in a tree that can recieve a hug. There’s nobody else there, so you’re basically hugging yourself. But what if the trees hugged back?

We do – most of us, anyway – love nature and feel that somehow our relationship with it is disrupted and needs to be repaired or reestablished. There are, of course, some people for whom a forest is nothing but a source of lumber and a dog is nothing but an annoyance. But they’re pretty rare. Just to take one example, how many millions of people keep pets? How many millions more would like to keep them if not for the hassle, cost, allergies, etc.? And why do we want pets? There’s no explanation other than a desire to have some part of nature that is personal enough to have a relationship with. We want to love nature, so we seek out something in nature that can love us back.

And love, the movie very wisely percieves, is the unique quality of humanity which nature utterly lacks. Sheer force is something nature has in plenty, as we see when the flood destroys the town. Beauty nature has in spades. Even intellect is present in nature to some extent, as many animals are capable of some degree of calculation. We can, of course, out-calculate them. But what really makes humanity stand out next to mere nature – the smallest taste of which is enough to drive Ponyo to turn the whole world upside-down rather than go without it – is love.

And let’s be clear that by “love” I’m not talking about mere gushy emotion or seniment. I mean a genuine desire for the good of others. In nature, mothers care for their young, and in one sense that’s love. But they only care for their young, not for others generally, and they do it in obedience to the maternal instinct. Doing good to another not because of any relationship we have with that other or to satisfy some instinct or desire of our own, but simply because we will the good of others – that’s something you’ll never find in nature.

Or should I say, something you’ll never find in nature except where humanity has affected it. Try getting a wild dog to love you. But tame the dog and it will love you as well as any person – because in the taming, the influence of human love pulls it upward into a real (though of course limited) state of personhood.

Naturally, humans being only human, we are never perfectly selfless and all our behavior is mixed with some level of wrongful selfishness. That’s what gives the cynics, like the sea-wizard, their excuse for disbelieving in the reality of love. And of course in some particular cases the cynics turn out to be right – many behaviors that look like love from the outside really aren’t. That is Sosuke’s test – does he really want Ponyo to have what’s good for Ponyo simply because it’s good for Ponyo and he desires Ponyo’s good as such?

It’s not a perfect movie. Just like in Miyazaki’s last work, Howl’s Moving Castle, the ending of Ponyo is rushed and forced. Miyazaki has bittten off so much he can’t quite resolve it all in the time he has available. And, I regret to say, over the years I think he has become increasingly hesitant to let anybody’s story end sadly – not just the heroes but anybody at all. In his greatest work, Princess Mononoke, good triumphs in the end and utter destruction is averted, but many good things are lost and the hero and heroine must give up something they dearly love in order to save their respective peoples. Even in his earlier family movies, there was loss and regret. But more recently Miyazaki has tried to arrange for everybody to end up well, and that gives his endings a false note.

But, like I said, plot is not the reason to go see Ponyo, and thus I think the problems with the ending detract little from the movie. Even if you get nothing but the fun story and the amazing visuals, it’ll be well worth the price of admission. And I think there’s a lot more than that to be had.

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

The headline in the New York Times says it all “Study Finds that Online Learning Beats the Classroom.”

Money quote:

“The study’s major significance lies in demonstrating that online learning today is not just better than nothing — it actually tends to be better than conventional instruction,” said Barbara Means, the study’s lead author and an educational psychologist at SRI International.

Echoes of Clayton Christensen, anyone?

I haven’t had a chance to read the study yet, but it looks like a meta analysis and finds:

Over the 12-year span, the report found 99 studies in which there were quantitative comparisons of online and classroom performance for the same courses. The analysis for the Department of Education found that, on average, students doing some or all of the course online would rank in the 59th percentile in tested performance, compared with the average classroom student scoring in the 50th percentile. That is a modest but statistically meaningful difference.

Nine national percentile points is a very large difference in my book. To put that in perspective, the highest scoring state in the country (MA) outscores the lowest (MS) by about 13.4% on the 4th grade reading NAEP.

I’ll write more after examining the study.

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

Big news out of Los Angeles- the school board has decided to emulate Philadelphia/New Orleans and outsource the management of 250 schools to charter operators, including several new multimillion dollar facilities. The LA Times reports:

“We’re here today to stand up for our children,” Villaraigosa told a cheering crowd while standing with about 25 students called up to appear with him. He stood under a banner proclaiming a “Parent Revolution,” which is the name of a parent-organizing campaign supported by leading charter school companies.

Outside the meeting room, waiting to get in, were both supporters and opponents of the resolution, written by Flores Aguilar. Labor unions, especially United Teachers Los Angeles, have opposed the measure, which Villaraigosa addressed in remarks that lasted about seven minutes.

“I am pro-union but I am pro-parent as well,” the mayor said. “If workers have rights, then parents ought to have rights too.” He added: “This school board understands that parents are going to have a voice.”

The Jurassic union thugs hate the proposal, but they got rolled. If you want to recall why, Drew Carey will give you a refresher:

My favorite part is when the union thug describes Steve Barr as “feeding at the public school trough” and “a vampire.” Paging Dr. Freud…we have a code red case of projection.

In any case, this is a BIG experiment in the nation’s second largest district. It will take skill and resolve to see it through. The reactionaries will be fighting it every step of the way. But for now, hats off to Mayor Villaraigosa, a former teacher union official, for showing the moral courage to take on the blob.

Public school systems have long hidden behind trumped-up claims of protecting student privacy to shield themselves from scrutiny for poor performance or misconduct, but this story from the world of higher ed really takes the cake.

The University of Central Arkansas (UCA) was in the practice of giving out “no-criteria presidential discretionary scholarships” totalling $1.6 million from 2006 until the program was ended this year. The no-criteria and discretionary feature of these scholarships are what have drawn concerns. Folks suspect that these scholarships were being given to the children of politically powerful people and other key allies to advance the political interests of this public, state university and/or the private interests of key trustees and school officials.

The suspicion that there was political hanky-panky in selecting who would be awarded these no-criteria scholarships has some support:

An Arkansas Democrat-Gazette review of hundreds of emails awarding the scholarships showed UCA handed them out often with no criteria, in wideranging amounts and under the occasional recommendation of high-profile people. Those who recommended recipients for the scholarships included the son of former Gov. Mike Huckabee, David Huckabee; state Sen. Steve Faris; former Arkansas House Speaker Benny Petrus; and some current and former UCA trustees.

There is no way to really investigate these concerns further because the university has refused to release a list of scholarship recipients. The U.S. Department of Education isn’t helping at all. In an advisory letter to UCA, the Department warned that “because the release of this type of scholarship information in personally identifiable form could be potentially harmful or an invasion of privacy, FERPA would preclude the University from disclosing this information without the prior written consent of the recipient.”

The U.S. Department of Education joins public schools in having a long track-record of being overly and selectively protective of student privacy. Universities regularly announce the names of recipients of scholarships. For example, a quick Google search finds that “The Graduate School of the University of Central Arkansas recognized Angela Quattlebaum and Jamie Martin as the 2004-05 recipients of the Robert M. McLauchlin Graduate Scholarship.”

How can those names be released but not the names of the no-criteria scholarship recipients? The logic, if you can call it that, is that a criteria-based scholarship is flattering to the recipient so that releasing the person’s name does no harm. A scholarship given for financial need or with no criteria might be embarrassing, so the names of the recipients of those scholarships cannot be released.

This makes no sense. Releasing the names of merit-based scholarship recipients still invades their privacy, even if with positive information. For example, the UCA announcement of the McLauchlin Graduate Scholarship provides all sorts of details, like “Angela Beth Quattlebaum is from Helena, Arkansas… She is the daughter of Terry and Monica Quattlebaum of Helena. In high school, she was a Girls State Delegate and listed in Who?s Who Among High School Students…” I strongly doubt that UCA received written permission from Ms. Quattlebaum before releasing all of this information about where she is from, who her parents are, and what she did in high school. I’m perfectly fine with it, but this hardly seems like protecting privacy.

On the other hand, refusing to provide information about no-criteria scholarship recipients may shield them from the release of embarrassing information. But that information would only be embarrassing if they were awarded these scholarships for reasons of political corruption. If that were the case it would be especially important that the public be informed about this even if it were embarrassing.

(edited for typos)

(Guest Post by Matthew Ladner)

I had a chance to watch the Fordham Foundation’s with ice cream ascendant is there a future for chocolate fudge event on charters and vouchers online. John Kirtley scored an early knockout when he noted that in Jacksonville Florida recently there all of 6 charter schools but 90 private schools serving low-income students through the Step Up for Students Tax Credit program. Kirtley then noted that not all 6 charter schools primarily serve low-income children. He likely could have added that not all six are high quality schools, but that would have been running up the score. Kirtley asked his debate opponents how much longer single mothers with children in the schools should have to wait for high quality school options.

DOWN GOES FRAZIER! DOWN GOES FRAZIER!

Kirtley’s opponents, Kevin Carey and Susan Zelman, raised the predictable totem of “accountability.” This of course is a real issue and a superficially powerful totem, but when you look behind the curtain, the Great and Powerful Oz is just an old man.

I live in a state where 44% of 4th graders scored below basic in 4th grade reading in 2007 and even a little worse in 2005. Who, pray tell, was held “accountable” for that sorry performance? Was a single administrator or teacher fired? Not that I am aware of. Did the public elect a new Superintendent of Public Instruction? Nope- the incumbent was reelected in 2006.

Who was held accountable? Try “not a single human being at all.” Public school “accountability” in short, is a cruel joke with kids as the victims.

Those who want to pretend that giving an all too often dummied down state test tied to a set of often sorry state academic standards constitutes “accountability” have confused their means with their ends. It isn’t the end all be all of accountability, nor is it necessarily really accountability at all.

Done well, I believe standards and testing can be a productive education reform. Choice programs however should be an opt-out of that system into one that is different, but which still contains a vitally necessary level of transparency. Something like the Stanford 10 will work nicely.

Kirtley’s point was the key: if we are really interested in helping disadvantaged children, all options must be on the table. Otherwise, pro-charter but anti-private choice folks do indeed come across like the gradualist white liberal wimps who urged the leaders of the civil rights movement to be “patient.”

Patience can be a virtue, but not when your hair is on fire.

One of the (many) problems with education policy analysts is that a large number of them live in or around Washington, D.C.

D.C. is a remarkably abnormal place. Because of the giant distortions of the presence and subsidies from the federal government as well as the atypical set of people who live in that area, policy experiences in DC are very often quite different from the experiences in the rest of the country.

The problem is that people tend to generalize from their immediate experiences. If something happens to you, you hear about it from people you know, or you read about it in your local paper, you tend to think that’s the way it is for everyone. So, DC education analysts are always at-risk of drawing policy conclusions based on incredibly atypical experiences.

For a prime example see Andy Rotherham and Sara Mead’s thoughts on special education vouchers:

In fact, if special education identification led to funding for private school attendance, it would be unusual if this did not create an incentive to participate in special education in many communities, particularly those with low-performing public schools. For example, Washington, D.C., and New York City currently contend with substantial abuse of special education by affluent parents. In addition, there are reports of parents seeking to have their students diagnosed with learning disabilities in order to gain accommodations on the SAT or for other reasons. [fn 27]

For another example, listen to Amber Winkler, Mike Petrilli, and Rick Hess discuss our most recent study on special education vouchers (it starts around minute 11:00). They generally do a good job of describing the study but they express doubts about our findings because they believe that parents, especially affluent parents, have considerable influence over special education placements.

On what basis do these D.C. education analysts believe that a significant number of parents, especially affluent parents, are gaming the special education diagnostic system to get access to advantageous accommodations or expensive private placements? The evidence Andy and Sara provide in footnote 27 consists largely of newspaper accounts from Washington, D.C.. Mike and Rick provide no source and we can only assume that they are drawing upon their immediate experiences.

Of course, the antidote to mistaken generalizations from our limited and potentially distorted set of immediate experiences is the reliance on systematic data. If we step back and look at the broad evidence, we can avoid some of the easy mistakes that result from assuming that everyone’s experience is like ours. As it turns out, DC is a gigantic outlier.

School officials, not parents, make the determination of whether a student has a particular disability and what accommodations are necessary. Parents are entitled to challenge the decisions of school officials, but they rarely do and even more rarely win those challenges.

In the fall of 2007 there were 6,718,203 students receiving special education services between the ages of 3 and 21. And that year there was a grand total of 14,834 disputes from parents resolved by a hearing or agreement prior to completion of a hearing (see Table 7-3). That’s about .2% of special education cases that are disputed by parents or 1 in 500.

And as Marcus Winters and I described in our new study, schools prevail in most of these disputes:

According to Mayes and Zirkel’s (2001) review of the literature, “schools prevailed in 63% of the due process hearings in which placement was the predominant issue.” In cases where the matter went beyond an administrative hearing and was actually brought to court, one study cited in Mayes and Zirkel’s review found that “schools prevailed in 54.3% of special education court cases,” which the authors say is in line with the findings of other studies. In suits seeking reimbursement for private school expenses (because a special-education voucher program is unavailable), Mayes and Zirkel found that “school districts won the clear majority (62.5%) of the decisions.

In addition, as Marcus Winters and I documented in a 2007 Education Next article, private placement is amazingly rare. Using updated national numbers from the federal government, as of fall 2007 there were 67,729 disabled students ages 6 through 21 who were being educated in private schools at parental request and public expense. That’s only 1.13% of the 6,007,832 disabled students ages 6 through 21 and barely one tenth of one percent of all public school students. If private placement supports Andy and Sara’s claim of “substantial abuse of special education” we’d have to redefine “substantial” to include minuscule proportions of students.

The systematic evidence clearly shows that school officials dominate special education, parents rarely challenge school officials’ decisions, schools win most of those challenges from parents, and parents very rarely get their children placed in private schools at public expense.

So, why do Andy, Sara, Rick, and Mike ( as well as all of those DC reporters who Andy and Sara cite) believe that parents, especially affluent parents, control special education decisions? Well, perhaps it is because in D.C. parents do have much more control than in the rest of the country.

Remember how there were 14,384 students nationwide who resolved a dispute with their school over special education in a hearing or by agreement prior to the completion of a hearing? DC contained 2,689 of those 14,384, or about 18% (see Table 7-3). But DC represents only .15% of total student enrollment nationwide. That means parents in DC are about 120 times more likely to lodge these challenges than the typical parent nationwide.

And while private placement is very rare, it is somewhat less rare in DC. Out of 67,729 students privately placed at parental request, 1,864 of them were in DC, or about 2.75% of the total. Again, given that DC student enrollment represents only .15% of national enrollment, DC students are about 18 times more likely to receive a private placement than students nationwide.

It’s clear that DC is just different — very different. Making generalizations from DC experiences or newspaper articles is like saying that Seattle is a sunny place if you happen to arrive there on a day when the sun was shining.

D.C. isn’t the only outlier. New York is also pretty atypical when it comes to special education. Dispute resolution hearings in New York state are about 7 times more common than in the rest of the country. And private placements are almost 3 times more common in the state of New York than they are nationwide.

It’s too bad that so many of our media and policy elites live in these two atypical places because they are giving us a very distorted picture of special education. They need to get outside of their bubbles and rely on systematic data rather than immediate experiences.

(Guest post by Greg Forster)

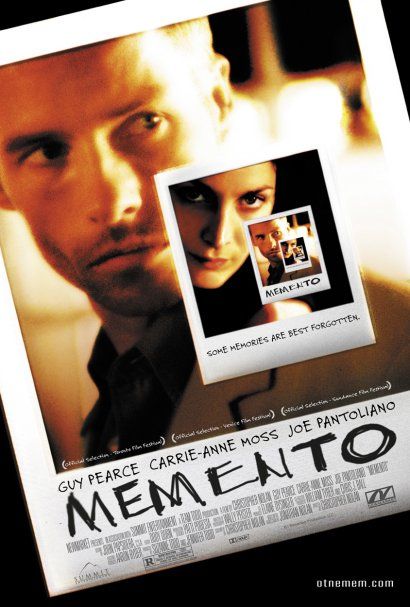

Hey, remember Memento?

No you don’t. You remember a really clever novelty act where they put you in the shoes of a man who can’t remember things that happen to him by telling most of the story backward. But memory is unreliable, remember?

Back when you saw it, you realized that it was – in addition to being a clever novelty act, which of course it was as well – a profound meditation on the nature of human identity – on the sources of knowledge, motivation, and “habit” or “instinct,” which together make up who we are.

But since then you’ve forgetten all that. What you retain all these years later is:

Okay, what am I doing? I’m chasing this guy.

No, HE’S chasing ME!

Which is just about the cleverest gag on film, I admit. But that’s a dog and pony show compared to this, which you don’t remember:

Just because there are things I don’t remember doesn’t make my actions meaningless. The world doesn’t just disappear when you close your eyes, does it?

You can question everything. You can never know anything for sure.

There are things you know for sure…Certainties. It’s the kind of memory you take for granted.

Of course, “earlier” (which is to say “later”) in the movie Leonard deprecates memory to Teddy. Memory is unreliable. You want facts, not memories. But now look at what Leonard tells Natalie – certainties are the kind of memory you take for granted. What is your knowledge of “the facts” but a bunch of memories? In which case, how can you know anything? As Augustine demonstrates at length in chapter 10 of the Confessions, memory comprises virtually all of the human personality.

It all comes down to whether or not you can take it for granted that there’s a real reality out there. Because if you can’t take it for granted, there’s no way to prove it. You can either assume it and be sane, or doubt it and go mad. That theme winds through everything in the movie. As Leonard tells Teddy at the “end” (which is to say at the “beginning”), whether or not he’s got the right John G. makes all the difference. It’s the only thing that matters.

But why? Teddy says we all just lie to ourselves to be happy. But Leonard knows that theory doesn’t hold water. If you really were lying to yourself, it wouldn’t make you happy. The fact that his quest for the killer does in fact motivate him proves that he’s not just interested in giving himself a purpose. He really wants to find the killer.

To Natalie, he simply asserts that the world doesn’t go away when you close your eyes. At the “end” (which is to say at the “beginning”) he pushes away the doubts Teddy has planted by insisting to himself that “I have to believe in a world outside my own mind.” That’s the rub. If you take that seriously – not “I have to believe” in the sense that I want to, so I’ll lie to myself to be happy, but “I have to believe” in the sense that my mind actually cannot function in any other way – it solves the problem.

To take a parallel example, no one can prove that two contradictory statements can’t both be true, for the simple reason that the activity of proving things itself assumes that two contradictory statements can’t both be true. The law of noncontradiction can’t be argued for or supported; we believe it because our minds simply will not function unless we do. You can either assume it unquestioningly or go mad; ultimately there are no other options.

But why, then, does the movie end (i.e. begin) the way it does? (For the sake of those benighted souls who may not have seen the movie, or for those who may have forgotten the details and may want to go back and see it again, I won’t spoil the central twist.) I think it’s simply that Leonard’s exchange with Teddy makes him realize that a man in his condition is unable to do what he’s trying to do, so he’ll do the next best thing – rid himself of the person who’s using him.

At any rate, I don’t think we’re meant to accept the claims we hear at the end about Leonard’s past. The movie itself undermines this in several ways. For starters, when those new “memories” start flashing into Leonard’s head, we get this image:

Which is obviously absurd and impossible. That’s the point – mere suggestion can produce new “memories” that feel accurate but can’t possibly be real. Which is why we have no reason to accept the new “memories” at the end.

Also, think about that pivotal image of Leonard lying on the bed when his wife says “ouch!” (If you don’t remember what I’m talking about, for goodness’ sake what more excuse do you need me to give you to go back and see this movie again!) If the new “memories” are real, then the revised version of this image must be the true one and the original version a construction. But the original version makes sense and the new one doesn’t. Why on earth would he do that in that contorted position? If he were going to [activity deleted to avoid spoiling the twist] he wouldn’t do it lying on the bed at a ridiculously awkward angle while she read a frikkin’ novel. But that’s exactly the kind of absurd image your mind would invent under a false suggestion.

Well, like my interpretation of the end or hate it, Memento is still one of the most profound movies out there, and it’s well worth a reviewing if you haven’t seen it since 2000.

Oh, and I hear Chris Nolan’s made some other interesting movies since then. Guess I should check those out.

HT Movie Images for most of these shots, Beyond Hollywood for the one at the top