(Guest post by Greg Forster)

A while back, noting Sen. Dick Durbin’s flagrantly false statements about the DC voucher study – he said the study didn’t show voucher students outperformed the control group, which is entirely true except for the fact that it did show voucher students outperforming the control group – Jay asked “is he stupid or lying?”

“Of course,” he added, “when it comes to an Illinois pol, one doesn’t have to choose. He could be both.”

Not long ago, when Sen. Durbin made similarly misleading (though now more carefully weaseled) statements in USA Today, Jay remarked, “I’m beginning to lean toward the lying end.”

The first sign of a good scientist is that he adjusts his theory in response to new data!

Well here’s another new datum to factor into our “stupid or lying” calculus. The AP reports that Durbin offered to help Rod Blagojevich make a deal for Barack Obama’s Senate seat. Take it away, AP (emphasis added):

CHICAGO (AP) – Just two weeks before his arrest on corruption charges, then-Gov. Rod Blagojevich floated a plan to nominate to the U.S. Senate the daughter of his biggest political rival in return for concessions on his pet projects, people familiar with the plan told The Associated Press.Blagojevich told fellow Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin he was thinking of naming Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan to the seat vacated when Barack Obama won the presidential election, according to two Durbin aides who spoke on condition of anonymity…The aides said the concessions Blagojevich wanted in return were progress on capital spending projects and a health care bill that were stalled in the Legislature…According to the Senate aides, Durbin was delighted to hear that Blagojevich was thinking of naming Madigan to the seat. He believed she would be a popular figure in Illinois and stood perhaps the best chance of holding the seat against a Republican.Durbin volunteered to call the attorney general or the speaker to get the ball rolling and possibly broker an agreement, the aides said.

When the AP came calling about the story, Durbin’s office offered no comment.

Moe Lane of Red State comments: “This would only be a bombshell if it had been unexpected…Senator Dick Durbin has had since November some very significant corroborating evidence that Governor Rod Blagojevich really was corruptly auctioning off a Senate seat. This is information that would have been very helpful when it came to the timing of Blagojevich’s impeachment, seating Burris, and/or fixing the entire problem with a special election. And yet, Durbin did or said nothing. I don’t wonder why. Then again, I know enough about this story to know that the Senator hadn’t realized that his talks with Blagojevich were being recorded.”

Lane highlights the implication that Durbin knew about Blago’s corruption all along, and kept vital information under his hat during the crisis. And Illinois-based politicians betraying the public trust by keeping vital information out of public circulation during a crisis does seem to be emerging as a meme in the DC voucher story.

But doesn’t it seem more important that AP is reporting Durbin offered to help broker the deal?

Yes, what Durbin offered to help arrange was not a bribe to be paid directly to Blago. It was conessions on Blago’s pet projects, including “capital spending projects.” Yet that’s bad enough, isn’t it? I’m aware that people take alliances and rivalries into account when they make these kinds of appointments. But isn’t it something else entirely to arrange a quid-pro-quo transaction of legislative votes for nominations?

And if you insist that there must be a personal bribe involved before we can say it’s wrong, let me ask you: given what we know about Blago, what kind of odds would you give that he wasn’t going to wet his beak on any of those “capital spending projects”? And doesn’t that make Durbin complicit? Or just how dumb are you willing to say Durbin is?

HT Moe Lane, via Jim Geraghty

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster

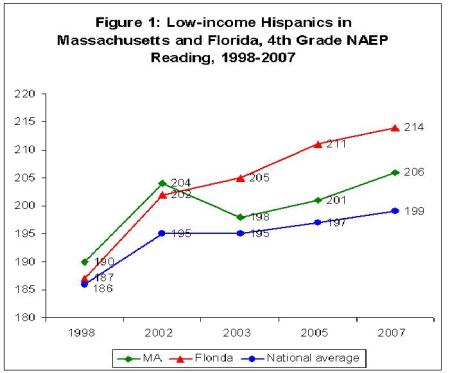

Again, MA doesn’t have anything to be ashamed of given their highest scores. There are other wealthy and homogenous states that spend a great deal on their public schools- and MA clobbers them. For me, however,

Again, MA doesn’t have anything to be ashamed of given their highest scores. There are other wealthy and homogenous states that spend a great deal on their public schools- and MA clobbers them. For me, however,