(Guest post by Greg Forster)

It’s taken me a week to think of it, but I have come up with what I believe is the ultimate nominee for the Al Copeland Humanitarian of the Year award this year. Or rather, two nominees.

Yes, the most interesting man in the world is . . . very interesting! I love the ads, but does he really represent the spirit of “The Al”? He certainly has done a lot of things – but what has he actually accomplished?

I propose that the true spirit of “The Al” is what you find inside . . . diapers.

Marion Donovan and Victor Mills’ diapers, to be exact.

Just spend a moment thinking about what life was like during the endless centuries when a diaper was nothing but a piece of cloth – one you had to wash and reuse, because manufactured goods couldn’t yet be made cheap enough for disposability. Contemplate, for a moment (but no longer than that!) how many diapers were changed from the first human beings technologically sophisticated enough to make clothing down through the middle of the twentieth century – and what was involved in changing each and every one of those diapers.

When Martin Luther wanted to illustrate the point that joyfully worshipping God was not a special activity that you did by going to church or performing other “religious works,” but something that had to infuse every single solitary human activity, even the most unpleasant, he was shrewd to choose diaper changing as an example:

Now observe that when … our natural reason … takes a look at married life, she turns up her nose and says, “Alas, must I rock the baby, wash its diapers, make its bed, smell its stench, stay up nights with it, take care of it when it cries, heal its rashes and sores, and on top of that care for my wife, provide for her, labour at my trade, take care of this and take care of that, do this and do that, endure this and endure that, and whatever else of bitterness and drudgery married life involves? What, should I make such a prisoner of myself? O you poor, wretched fellow, have you taken a wife? Fie, fie upon such wretchedness and bitterness! It is better to remain free and lead a peaceful. carefree life; I will become a priest or a nun and compel my children to do likewise.”

He went on to focus on diaper-changing as the representative activity encompassing all these unpleasant duties. Luther knew that by sticking up for the honor of the married estate, he was sticking up for getting poop on your hands. Daily.

But having a family doesn’t mean daily poop-scrubbing anymore.

Born in 1917, Donovan spent much of her childhood hanging around the Ft. Wayne factory run by her father and uncle. They were inventors in their own right – having invented, among other things, an industrial lathe for making automotive gears and gun barrels – and she absorbed their entrepreneurial spirit.

Her first invention was a waterproof diaper cover, made out of a shower curtain, to contain the small leaks that were endemic to diapers in the pre-Donovan era. Rubber baby pants were already on the market, but they weren’t widely used because they caused diaper rash and pinched the skin. The plastic “changing pads” we use today are a distant descendant of Donovan’s innovation.

For good measure, she put snaps on her diaper cover instead of using safety pins, which at the time were the universal fastening technology in the diaper sector. Today we use velcro, but the original quantum leap away from the use of dangerous and labor-intensive pins was Donovan’s.

None of the big manufacturers would even consider marketing her invention, so she went into business for herself. Her product was an overnight success, debuting at Saks Fifth Avenue in 1949. After two years she sold it to one of those super-smart manufacturing companies that had been too dumb to give her the time of day back when it would have counted.

Like any good entrepreneur, she didn’t rest on her laurels but plowed her success into the next innovaiton – this time, disposable diapers. The challenge was significant; she needed to make the interior out of paper (so it would be cheap enough to manufacture in large numbers) but make it durable and absorbant.

She produced what she thought was a workable solution, but once again she couldn’t get the manufacturers interested. They were already working on the same idea – and Victor Mills, a chemical engineer at Proctor & Gamble, had a better solution than hers. (Those are the breaks! “The Al” celebrates the tough life of entrepreneurial struggle.)

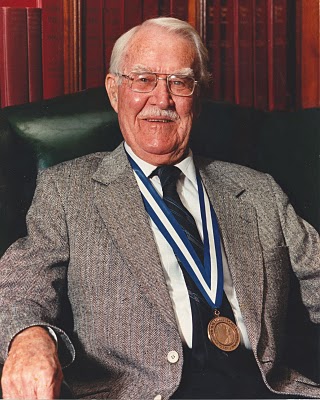

In 1956, P&G had acquired a new paper pulp plant, and it asked Mills and his team what they could do with it. Lots of companies were working on disposable diapers, but nobody had solved the problem yet. Mills, a grandfather at the time, had a pretty strongly vested interest in coming up with a solution. And the new plant yeilded just enough durability and absorbancy to solve the problem. Using his grandchild to test the prototypes, Mills developed the disposable diaper that ultimately became Pampers in 1961.

Well earned

So if you have kids, thank Donovan and Mills for their contribution to your well-being – and vote for them for Al Copeland Humanitarians of the Year.

HT Thomas Frey, Women Inventers and Chemical Engineering World for images, Famous Women Inventors and Jon Marmor for info

Posted by Greg Forster

Posted by Greg Forster